|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

| 글로벌 트렌드 | 내서재담기 |

|

|  |

자연 친화적 업무 환경의 청사진

자연 친화적 업무 환경이 개인에게는 행복감과 만족을, 조직에게는 높은 생산성을 보장하고 이직을 방지하는 효과를 내고 있다. 이를 알아 본 조직들은 이전부터 업무 환경에 자연을 대비시키고 있다. 실제로 어떤 것들이 있으며, 실제 효과는 어떠할까?

평균적으로 우리는 생활의 약 92%를 실내에서 보낸다. 그러나 이른바 바이오필리아 가설(biophilia hypothesis)에 따르면, 인간은 자연적 요소 및 그 과정과 접촉하려는 강한 본능적 욕구를 가지고 있다. 각종 연구는 우리가 그 욕구를 충족시킬 때 일반적으로 다음과 같은 결과를 얻는 것으로 보고 있다.

- 더 큰 활력과 의지를 경험하고,

- 정신적으로 더 명료해짐을 느끼고,

- 돕고자 하는 행동이 더 증가한다.

그러나 그 반대의 경우, 스트레스와 우울증, 공격성에 더 취약한 상태가 된다.

이러한 현상이 업무 성과에 미치는 영향을 고려해보자.

업무는 그것이 원격인지 현장인지와 상관없이 대부분 사람들을 실내에 있게 한다. 이에 고용주들이 내근 직원들이 자연과 격리된 공간으로 인해 발생하는 문제들을 완화시킬 수 있음을 인식하고, 소위 자연 친화적 업무 설계를 통해 자연적 요소들을 직원들의 일상 활동 및 업무 공간에 통합하기 시작했다. 이러한 노력은 매우 광범위하게 일어나고 있다.

어떤 기업들은 직원들이 미팅을 가지거나 전화를 할 때 활용할 수 있는 매우 매력적인 야외 공간을 제공하는 것과 같이 직접적으로 자연적 요소를 제공하고, 또 다른 기업들은 전면적 뷰(view)를 가진 큰 창문과 같은 방식으로 직원들을 간접적으로 자연에 노출시키기도 한다.

원격 근무자의 경우, 물리적 시설에 대한 변화를 고용자가 컨트롤할 순 없지만, 다른 방식으로 직원들을 지원할 수 있다. 예를 들어, 직원들이 재충전을 할 수 있도록 야외 산책을 권장할 수 있고, 날씨가 좋을 때는 노트북을 가지고 외부에서 일하도록 할 수 있다. 더불어, 자연 배경을 가진 ‘가상 회의실’은 디지털 방식으로 실제 자연의 효과를 제공해줄 수도 있다.

몇몇 조직은 직원의 복지와 근속률 유지를 위해 자연 친화적 업무 환경 설계를 채택하고 있지만, 이로 인한 혜택은 사실 그것보다 훨씬 더 크다. 텍사스 A&M 대학교의 앤서니 C. 클로츠(Anthony C. Klotz) 교수와 오클라호마 대학의 마크 볼리노(Mark Bolino) 교수에 따르면, 직원들이 자연 환경과 더 자주 그리고 더 밀접하게 상호 작용하도록 하면 직원들의 에너지와 업무 생산성을 높일 수 있다. 이는 결국 기업의 수익성에도 큰 영향을 미치게 된다.

그렇다면 현재 고용주들이 시작한 변화에는 어떤 것들이 있을까?

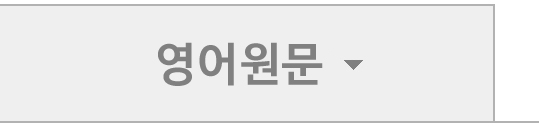

직원들이 자연에 직접적으로 노출되도록 만드는 업무 공간이 직원들의 자연 친화적 욕구를 가장 크게 만족시킬 수 있다. 직접적인 노출의 일반적 사례는 직원들이 야외에서 휴식을 취할 수 있도록 녹색 옥상 테라스와 같은 공간을 제공하는 것이다. 한국의 삼성전자는 이것보다 더 진일보한 조치를 취했다. 캘리포니아 산호세에 있는 신축 10층의 R&D 본사는 3층마다 옥외 정원 층을 설치했다. 직원들이 옥외 정원과 한 층 이상 떨어져 있지 않도록 한 조치이다. 또 다른 조직들은 다양한 인적 자원 혜택을 통해 직원들이 야외로 나가도록 장려하고 있다. 예를 들어, 아웃도어 브랜드 REI의 전 직원들은 1년에 두 번의 ‘야호 데이즈(Yay Days)’를 받을 수 있습니다. 이 휴가 기간은 야외에서 보내야 함을 의미한다. 마찬가지로 선글라스 제조업체 오클레이(Oakley)는 직원들에게 스키 패스를 제공하여 야외에서 시간을 보내도록 권장하고 있다.

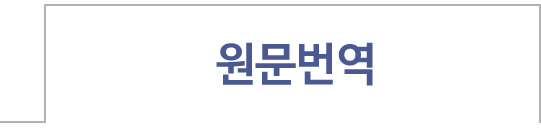

실외에 있는 것만큼은 아니지만, 자연적인 요소를 실내로 가져 오면 직원들이 자연과 직접 접촉 할 수 있다. 시애틀에 있는 아마존 본사(Amazon Spheres) 건물은 실내 열대 우림과 사무 공간 사이의 경계를 모호하게 한다. 다소 덜 극단적인 방식으로 이들은 ‘살아있는 벽’을 활용한다. 업무 공간을 설계할 때 아마존은 토양 지반의 벽에서 식물이 자라도록 했다. ‘살아있는 벽’은 뉴욕 브루클린에 위치한 전자상거래 사이트 엣시(Etsy)의 새로운 본사 9개 층에서도 찾을 수 있다.

안타깝게도 자연에 직접적인 노출이 항상 가능한 것은 아닐 것이다. 이러한 경우 고용주는 창문뿐만 아니라 자연적 요소를 표현한 인공물, 또는 그러한 요소를 사용한 건축 자재를 통해 간접적인 노출을 제공할 수도 있다. 위스콘신의 건축가 프랭크 로이드 라이트(Frank Lloyd Wright)가 설계한, 러신(Racine)에 위치한 SC 존슨 본사(SC Johnson Administration Building)는 나무 모양 기둥이 건물의 거대 업무 공간(Great Workroom)을 받치고 있는데, 이 기둥들은 열린 대초원(savanna)에서 보이는 그늘을 형성해주는 나무들을 기능적, 형태적으로 모방한 것이다. 자연에 대한 간접적 접촉의 보다 일반적인 사례로는, 자연적 요소를 묘사한 벽지 또는 벽화, 천연 재료로 만든 바닥재가 있다.

어떤 경우에는 디지털 도구가 자연과의 상호 작용을 시뮬레이션하거나 촉진하는 데 사용된다. 샌프란시스코에 위치한 세일즈포스닷컴(Salesforce.com) 본사를 방문하면, 직원들은 강, 숲, 폭포를 고화질로 보여주는 108 피트 규모의 비디오 벽면을 지나갈 수 있다. 마찬가지로 건축 회사 쿡폭스(Cookfox)의 맨해튼 사무실에 있는 디지털 공기 모니터는 높은 수준의 이산화탄소 또는 오염 물질이 감지되면 신선한 공기를 업무 공간으로 내보낸다. 자연의 소리를 녹음하여 개방형 사무 환경 곳곳에서 틀어주는 사례도 많아지고 있다.

자연과 직간접적으로 다양하게 연계하고 있는 기업들은 직원들의 복지와 근속률을 높이기 위한 방법으로 자연 친화적인 설계를 채택했다고 말하고 있다. 이는 직장에서 녹지 공간에 대한 접근성을 제공할 때 발생하는 이득에 대한 기존 연구와 일치한다.

예를 들어, 유기농 식음료 기업 클리프 바(Clif Bar)가 자연 친화적 원칙을 기반으로 설계한 아이디오 베이커리(Idaho bakery)를 열었을 때, CEO 케빈 클리어리(Kevin Cleary)는 다음과 같이 말했다.

“우리는 사람들이 건강하고 친근하게 일할 수 있는 장소가 되길 원한다. 우리 직원들, 커뮤니티, 지구를 유지 가능하게 하는 업무 공간이 그것이다.”

애플(Apple)의 새로운 본사에 있어 가장 중요한 요소에 대해 물었을 때, 수석 디자이너 노만 포스터(Norman Foster)는 ‘건물 주변의 자연, 경관과의 강력한 연계’에 집중했다고 밝혔다. 그는 직원들이 신선한 공기를 마시고, 야외와 하늘을 볼 수 있을 때 '더 생산적이며, 더 깨어 있고, 위기에 더 훌륭하게 대응’을 할 수 있다고 말했다.

현장 연구는 다양한 방식의 자연 친화적 설계가 직원들의 업무 성과를 높였음을 실질적으로 입증하기 시작했다. 직장 내에서 자연에 대한 노출이 부족하면 ‘업무 불만족’, ‘번아웃(burnout, 소진)’과 같은 부정적 결과로 이어진다는 초기 연구 성과물만 고려해도, 이러한 결과를 기대하는 것이 결코 과한 것은 아닐 것이다. 그리고 디지털 세계에서, 자연과의 접촉은 ‘초연결성’, ‘멀티 스트리밍’, ‘원격 근무’, ‘애자일 매소드(agile method, 프로젝트 관리 방법 중 하나)’, 그리고 직원들의 몸과 마음을 인공적인 영역으로 더 깊이 끌어들일 수 있는 ‘기타 디지털의 특성’이 가져오는 영향에 대해 건강한 균형을 맞추는 데 특히 중요한 역할을 해줄 수 있다.

직원들을 자연에 더 많이 노출시킴으로서 얻는 이득은 현재 조직이 알고 있는 것보다 훨씬 더 크다. 자연과의 상호 작용은 인지적, 정서적, 친교적, 신체적 이 네 가지 방식으로 직원들의 에너지 보유량을 높일 수 있는 잠재력을 가지고 있다. 그러나 이러한 혜택을 누리려면 단순히 직원들을 자연과 접하게 하는 것만으로는 충분하지 않다. 따라서 리더는 이를 신중하게 수행해야 한다.

다음 사례를 보자. 사무실 내 자연적 특성은 설계대로 고정된 경우가 많다. 그러나 퀘벡 시티에 있는 웹 호스팅 회사 OVH의 사무실은 크지만 이동 가능한 화분을 사용하여 직원들이 자연과의 근접성을 자신들의 근무 상황과 그들 스스로의 취향에 맞추도록 하고 있다. 업무 공간 디자인에 직원을 참여시키는 조직들은 개인의 고유한 욕구에 맞게 자연과의 접촉 상황을 조정할 수 있다. 워싱턴 벨뷰(Bellevue)에 위치한 REI의 새 본사에서는 ‘모든 야외’ 인프라가 설계 및 구축되었으며, 외부로 통하는 복도와 회의실의 롤업 도어를 통해 연중 야외 회의가 가능하다. 공간 구성 세부 사항을 포함하는 디자인의 마지막 20%는 미완성 상태로 남겨두었다. 이러한 방식으로 REI의 직원들은 자신의 업무 공간을 자신에게 맞출 수 있을 뿐만 아니라 전체로서의 옥상 녹지 공간과 같은 공용 영역도 맞춤화하여 종합적인 자연 친화적 욕구를 맞출 수 있다.

수세기 동안 철학자들은 자연 세계와의 연결의 미덕을 칭찬해 왔다. 하지만 조직 리더들은 최근 몇 년전부터 이 지혜를 받아들이기 시작했다. 자신들의 업무 공간, HR 실무, 문화 규범을 진화시키는 데 현명한 투자를 하려면, 이제 리더들은 자연 친화적 업무 환경 설계의 효과가 여러 수많은 요소들에 달려있음을 이해해야 한다. 그 요소들은 자연에 대한 직간접적 노출, 자연적 요소의 형태들과 통합, 심리적 환경, 업무 환경 설정에 있어서의 조직 문화, 업무 공간 설계에 대한 참여, 개인마다 다른 욕구 등 매우 다양하다. 이러한 요소들이 신중하게 고려되면, 이점을 극대화할 수 있다.

이러한 추세를 고려하여, 우리는 향후 다음과 같은 예측을 내려볼 수 있다.

첫째, 자연과의 접촉을 강화하는 기업은 직원들의 업무 집중 능력을 향상시킬 수 있을 것이다.

이는 부분적으로는 재충전 효과가 있기 때문이다. 더불어 사람들의 의지력도 회복시킨다. 마치 운동을 위한 휴식이나 명상과 같다. 그러나 또 다른 이유도 있다. 주의를 부드럽게 유지하는 자연과의 접촉은 부담을 주지 않는 방식으로 인지 기능을 향상시킬 수 있다. 옥상 테라스에서 휴식을 취할 때 직원들은 이러한 요소에 관심을 크게 집중하지 않고도 신선한 공기와 태양의 정신적으로 충만해지는 에너지 효과를 즐길 수 있다. 물론 모든 형태의 자연 노출이 인지 에너지에 동일한 영향을 미치는 것은 아니다. 안소니 클로츠와 마크 볼리노는 반복적 혹은 지속적으로 노출이 된 후에는 정적 요소들의 효과가 중단되는 경향이 있기 때문에, 자연적 요소는 시간이 지남에 따라 정적이 아니라 동적일 때 사람들의 관심을 끌기 더 쉽다고 제안한다. 따라서 인도 구르가온(Gurgaon)에 있는 SAP 사무실과 같은 환경에서는 매립 목재 바닥과 같은 정적인 자연친화적 특성과 함께 대형 수족관이나 식물 벽과 같은 역동적인 자연적 요소를 필요로 하였다. 이러한 동적 기능은 재생 목재와 같은 정적 요소보다 직원의 정신 에너지에 더 많이 기여할 것으로 기대할 수 있다.

둘째, 업무 공간과 떨어진 자연과의 접촉을 성공적으로 장려하는 기업은 직원들에게 정서적으로 활력을 불어 넣어 더 나은 성과로 이어지는 효과를 볼 것이다.

업무 공간과 떨어진 자연과의 접촉을 강화하는 것은 심리적 휴가를 취하는 것과 같으며, 기분 전환, 정서적 피로 감소와 같은 실제 휴가와 연계되는 효과를 얻게 할 수 있다. 몇몇 기업들은 업무 현장에서도 직원들에게 자연에 기반한 ‘업무 공간에서의 심리적 탈출’을 제공하기 위해 많은 노력을 기울여왔다. 취업 전문 사이트 인디드(Indeed)의 새로운 도쿄 사무소에는 나무, 이끼, 바위로 둘러싸인 휴식과 업무를 위한 작은 지역으로 자연친화적 오아시스 공간을 제공한다. 그러나 중요한 것은 다른 근무 조건에서 결핍이 있다면, 이러한 효과는 사라질 것이란 점이다. 예를 들어, 직원을 학대하는 관리자가 있거나, 모욕적인 업무를 취급하게 하는 경우, 자연 친화적 업무 환경 설계만으로는 기업들이 얻고자 하는 바를 기대할 수 없을 것이다.

셋째, 자연 친화적 업무 환경을 구축하면, 타인을 돕고 직장뿐만 아니라 다른 곳에서도 긍정적 관계를 구축하고자 하는 직원들의 욕구를 더 높여줄 것이다.

자연계 모든 요소들 - 우리 모두가 숨 쉬는 공기, 우리 모두가 보는 태양 등 - 간의 연결성을 감안할 때, 자연에 대한 노출은 주변 세계, 다른 사람들과 하나가 되는 느낌을 줄 것이다. 결국 이러한 감정은 관대함과 협동심을 증가시킬 수 있다. 실제로 사람들이 자신을 자연 세계의 일부라고 느끼는 만큼 다른 사람의 관점에 개방적일 가능성이 높다. 이러한 이점을 염두에 두고 자연 친화적 업무 환경 요소를 설계할 수 있다. 예를 들어, 런던에 위치한 모건 신달 그룹(Morgan Sindall Group)의 새 본사에서 중심적인 디자인 기능은 나뭇가지가 건물 전체에 걸쳐있는 거대한 인공 나무이다. 다만, 이러한 업무 공간 디자인 요소의 친사회적 영향은 새로운 이메일이 도착했다는 끊임없는 신호음과 같은 ‘부자연스럽고 불편한’ 방해로 인해 약화될 수 있다. 따라서 더 넓고 큰 세상이 아닌 업무에서 발생하는 미시적 영역에 주의가 집중되지 않도록 고려하는 것이 좋다.

넷째, 야외에 있으면 생리적 건강과 활력에 관련된 호르몬 수치가 높아진다. 단, 이것은 개인마다 차이가 있다.

연구에 따르면 자연의 신체적 에너지 효과는 개인이 자연 세계와 연결되기를 원하는 정도에 따라 달라진다고 한다. 바이오필리아 가설은 모든 개인이 자연과 연결하려는 타고난 욕망을 가지고 있다고 예측하지만, 이 욕망의 힘은 사람마다 다르다. 또한 모든 직원이 직장에서 자연과의 특정 형태의 접촉으로 똑같이 활력을 느끼는 것도 아니다. 따라서 자연을 바탕으로 한 업무 환경 디자인은 직원의 자연 친화적 욕구와 물리적 작업 환경 사이에서 양립성을 반드시 추구해야 한다.

* *

References List :

1. MIT Sloan Management Review. May 04, 2020. Anthony C. Klotz. Creating Jobs and Workspaces That Energize People.

https://sloanreview.mit.edu/article/creating-jobs-and-workspaces-that-energize-people/

2. com September 2018. Kenneth Freeman. Enriching The Workplace With Biophilic Design.

https://www.workdesign.com/2018/09/enriching-the-workplace-with-biophilic-design/

3. Space. February 6, 2019. Cecilia Amador de San José. 5 WAYS TO EMBRACE BIOPHILIA IN THE WORKPLACE AND WHY YOU SHOULD.

https://allwork.space/2019/02/5-ways-to-embrace-biophilia-in-the-workplace/

4. com. March 28, 2019. Mike Steere. Biophilic design: Why nature could be a good investment.

https://www.cnn.com/2019/02/22/intl_business/biophilic-design-healthy-employees/index.html

|  |

The Promise of Biophilic Work Design

On average, we spend about 92% of our lives indoors. Yet, the so-called biophilia hypothesis suggests that humans have a strong innate desire to be in contact with natural elements and processes. Research suggests that when we fulfill that desire, we typically

• experience greater vitality and willpower,

• feel a sense of mental clarity, and

• engage in increased helping behavior.

However, when we don’t, we are more susceptible to stress, depression, and aggressiveness.

Consider the implications which this phenomenon has for work performance.

Many jobs require people to be indoors, whether the work is done remotely or onsite. Recognizing that they can help alleviate the problems associated with nature-free space for onsite workers, employers, have begun to incorporate aspects of nature into employees’ day-to-day activities and workspaces through the so-called “biophilic work design.” These efforts are wide-ranging.

At one end of the spectrum, companies provide direct immersion using natural elements such as providing employees with an appealing outdoor space where they can conduct meetings or phone calls. At the other, we have indirect exposure which includes having large windows with sweeping views.

In the case of remote workers changes to physical facilities are not as controllable. However, these workers can be supported in other ways. For instance, managers can encourage people to take walks outdoors to recharge and to bring their laptops outside when weather permits. Meanwhile, "virtual meeting rooms” with natural backdrops can serve as digital proxies for windows.

While some organizations are embracing biophilic work design for the sake of employee well-being and sustainability, the benefits go even further than that. According to Professors Anthony C. Klotz of Texas A&M and Mark Bolino of the University of Oklahoma, helping employees interact more frequently and closely with the natural world can boost their energy and thus their work productivity. And this ultimately impacts the bottom line.

What sorts of changes have these employers already begun to make?

Jobs and workspaces that allow employees to engage with the natural world through direct exposure are able to most thoroughly satisfy employees’ biophilic desires. A common example of direct exposure is providing workers with spaces such as green rooftop terraces where they can take outdoor breaks. Samsung has taken this concept further than most: In its new 10-story R&D headquarters in San Jose, California, every third floor is an open-air “garden floor,” which ensures that employees are never more than one story away from an outdoor space. Other organizations are encouraging workers to get outdoors through various human resources perks. For instance, every worker at REI is entitled to two “Yay Days” per year; these vacation days are explicitly meant to be spent outside. Similarly, Oakley, the sunglasses maker, gives its employees ski passes, which encourage them to spend time outdoors.

Although not as deeply engaging as being outdoors, bringing natural elements indoors can still give employees direct contact with nature. The Amazon Spheres building in Seattle blurs the line between indoor rainforest and office space. A less extreme approach is the use of "living walls," which are soil-based walls with plants growing on them, in the design of many workspaces. For instance, living walls can be found on all nine floors of Etsy’s new headquarters in Brooklyn, New York.

Unfortunately, direct exposure to nature isn’t always feasible. In those cases, employers can provide indirect exposure not just through windows but also via human-made representations of natural elements or building materials that use those elements. In the SC Johnson Administration Building in Racine, designed by Wisconsin’s Frank Lloyd Wright, tree-shaped columns in its Great Workroom mimic (in form and function) shade trees found on an open savanna. More conventional examples of indirect contact include wallpaper or murals that depict natural elements or floor coverings made of natural materials.

In some cases, digital tools are being used to simulate or promote interaction with nature. Upon entering the main offices of Salesforce.com in San Francisco, employees pass by a 108-foot video wall that streams footage of rivers, forests, and cascading water in high definition. Similarly, digital air monitors in the Manhattan offices of the architectural firm Cookfox direct fresh air into workspaces when high levels of carbon dioxide or pollutants are detected. And recorded nature sounds are increasingly being played in open-office settings.

Wherever they fall along the direct-to-indirect continuum, companies typically state that they are embracing biophilic design as a way to increase employee well-being and promote sustainability. That jibes with existing research on the benefits of providing access to green spaces at work.

For example, when Clif Bar opened its Idaho bakery, which was designed using biophilic principles, CEO Kevin Cleary said, “We wanted it to be a healthy, welcoming place for people to work — a workplace that sustains our people, the community, and the planet.”

When asked about the most important element of Apple’s new headquarters, lead designer Norman Foster focused on the “strong connection with nature and the landscape surrounding the building,” adding that when employees can “breathe fresh air and see the outdoors and the sky, you’re more productive, more alert, and better able to respond to crises.”

Field studies have only begun to empirically demonstrate that biophilic design has improved employee performance in these ways. But it’s not a stretch to expect such outcomes, given the findings of initial studies linking a lack of exposure to nature at work to adverse consequences such as job dissatisfaction and burnout, which are robust predictors of poor performance and counterproductive behavior. And in a digital world, contact with nature may play a particularly important role in counterbalancing the effects of hyperconnectivity, multistreaming, remote work, agile methods, and other job characteristics that can pull employees’ bodies and minds deeper into the realm of the artificial.

Indeed, the gains from increasing employees’ exposure to nature may be even richer than organizations currently realize. Interactions with nature have the potential to boost employees’ energy reserves in four ways: cognitively, emotionally, prosocially, and physically. However, to reap these benefits, it is not enough to simply place employees in contact with nature; leaders must do it thoughtfully and avoid countering the potential gains with other choices they make about job and workspace design.

Consider this example: Whereas natural features in offices are often stationary, the offices of web hosting company OVH in Quebec City use large but movable planters to allow employees to customize their proximity to nature while at work. Organizations that engage employees in the design of their workplaces can tailor contact with nature to individuals’ distinctive desires. At REI’s new headquarters in Bellevue, Washington, an “everything outdoors” infrastructure was designed and built, complete with hallways open to the outside and roll-up doors in conference rooms to allow year-round open-air meetings. The final 20% of the design, which involves space configuration details, was left unfinished. This way, REI’s employees can not only customize their own workspaces but also, as a group, customize common areas, such as the rooftop green space, to align with collective biophilic desires.

For centuries, philosophers have extolled the virtues of connecting with the natural world—but organizational leaders have just begun to embrace this wisdom in recent years. To make smart investments in updating their workspaces, HR practices, and cultural norms, leaders should understand that the effects of biophilic work design can depend on a number of factors: such as whether the exposure to nature is direct or indirect, the types of natural elements incorporated, the psychological climate, the organizational culture of the work setting, and the ability to tailor workspaces to suit individual differences in biophilic desires. When these factors are thoughtfully considered, the benefits can be maximized.

Given this trend, we offer the following forecasts for your consideration.

First, companies that embrace enhanced contact with nature will benefit from employees’ increased ability to concentrate on work tasks.

That’s partly because it has a recharging effect; it restores people’s willpower, much like breaks for exercise or meditation during the workday do. But there’s another reason as well: Contact with nature that gently holds one’s attention can enhance cognitive functioning in a way that is not taxing. When taking a break on a rooftop terrace, employees can enjoy the mentally energizing effects of fresh air and the sun without having to focus their attention on those elements. — However, not all forms of exposure to nature seem to have equivalent effects on cognitive energy. Anthony Klotz and Mark Bolino suggest that because we tend to tune out static things after repeated or ongoing exposure, natural elements are more apt to hold people’s attention if they are dynamic rather than static over time. So, in settings such as SAP’s offices in Gurgaon, India, which include static biophilic features like reclaimed-wood floors, there is a need for dynamic natural elements like large aquariums and plant walls. Such dynamic features can be expected to contribute more to employees’ mental energy than static elements like reclaimed wood.

Second, companies that successfully encourage enhanced contact with nature away from the workplace will emotionally energize employees leading to better performance.

Enhanced contact with nature away from the workplace is like taking a psychological vacation and it allows people to gain at least some of the benefits associated with real vacations, such as improved mood and reduced emotional exhaustion. Some companies have gone to great lengths to give workers nature-based "psychological escapes from the office" even on-site. Indeed’s new Tokyo offices include biophilic oasis spaces, small areas for both relaxation and work that are surrounded by trees, moss, and rocks. Importantly though, if other work conditions are deficient, that can thwart employees’ ability to “getaway.” For example, if an employee has an abusive manager or is given demeaning job tasks, no amount of biophilic work design will allow him or her to emotionally escape that reality.

Third, introducing biophilic work elements will boost employees’ desire to help others and build positive relationships at work and elsewhere.

Given the connectedness among elements in the natural world — the air we all breathe, the sun we all see, and so on — exposure to nature may prompt feelings of oneness with the world and with others. Such feelings, in turn, can increase generosity and cooperation. Indeed, to the extent that people feel they are part of the natural world, they are more likely to be open to others’ perspectives. Biophilic work elements can be designed with those benefits in mind. For instance, at the new headquarters of Morgan Sindall Group in London, the central design-feature is a massive “engineered tree” whose branches reach out across the entire building. Unfortunately, the prosocial impact of such work design elements may be undermined by a barrage of unnatural and unpleasant intrusions, such as the constant pinging of new emails. After all, such intrusions tend to focus our attention on the “micro” aspects of work, rather than the broader world. And,

Fourth, being outdoors will boosts levels of hormones associated with physiological health and vitality, but the benefits will vary among individuals.

Research shows that the physically energizing effects of nature differ based on the degree to which individuals yearn to connect with the natural world. Although the biophilia hypothesis predicts that all individuals have an innate desire to connect with nature, the strength of this desire differs from person to person. What’s more, not all employees will feel equally vitalized by a given form of contact with nature at work. So, nature-based work design should strive for compatibility between employees’ biophilic desires and the physical work environment.

References

1. MIT Sloan Management Review. May 04, 2020. Anthony C. Klotz. Creating Jobs and Workspaces That Energize People.

https://sloanreview.mit.edu/article/creating-jobs-and-workspaces-that-energize-people/

2. com September 2018. Kenneth Freeman. Enriching The Workplace With Biophilic Design.

https://www.workdesign.com/2018/09/enriching-the-workplace-with-biophilic-design/

3. Space. February 6, 2019. Cecilia Amador de San José. 5 WAYS TO EMBRACE BIOPHILIA IN THE WORKPLACE AND WHY YOU SHOULD.

https://allwork.space/2019/02/5-ways-to-embrace-biophilia-in-the-workplace/

4. com. March 28, 2019. Mike Steere. Biophilic design: Why nature could be a good nvestment.

https://www.cnn.com/2019/02/22/intl_business/biophilic-design-healthy-employees/index.html