|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

| 글로벌 트렌드 | 내서재담기 |

|

|  |

미국 내 도시 인구의 유입과 유출에 있어 패턴 변화가 일어나고 있다. 코로나19는 이러한 패턴 변화를 더욱 가속화하고 있다. 어떤 도시와 지역에 인구가 늘고, 주는가? 이유는 무엇인가? 이러한 패턴 변화는 어떤 결과를 가져올 것인가?

.png)

거대 도시화의 추세에 대해, 소위 전문가들은 OECD 국가들 내 특정 밀집된 대도시들이 계속 성장하고 있다는 근거로, 개발도상국들 또한 사람들이 빈곤한 농촌으로부터 대도시로 계속 이동할 것이라고 주장해왔다. 그런데 대도시의 생산성이 그 외 지역보다 확실히 높을까? 그렇지는 않은 것 같다. 데이터를 분석할 때 분석자의 편견으로 인해 수많은 혼란이 발생하곤 하는데, 경제적 측면에서 ‘밀집된 도시 지역이 매우 생산적’이라는 자주 인용되는 주장도 그중 하나다. 실제로 데이터가 정확하게 분석되었을 때 그것은 사실이 아닌 것으로 판명되었다.

그럼에도 불구하고 한 세대에 걸쳐 전문가, 광고 홍보 기관, 부동산 투기자들의 행렬은 미래가 주로 밀집된 곳에 ? 특히 해안선을 낀 대도시권의 중심 도시 ? 있음을 강조해왔다. 실제로, 불과 10년 전 금융 위기 속에서 교외 지역의 미래는 위험해 보였고, 전문가들은 수많은 교외 인구 조사 결과가 다음 슬럼가가 어디가 될 것인지를 명확하게 보여준다고 주장했다. 오바마 행정부의 주택도시개발부 장관은 무질서하게 뻗어 나간 도시 외곽 지역이 이제 문제에 봉착했고 사람들이 대도시권의 중심 도시로 다시 회귀하고 있다고 선언한 바 있다. 현실과 다르다는 점에서 이는 미국이 에너지 독립을 이루지 못할 것이고, 미국의 제조업 일자리는 다시 부흥하지 않을 것이라는 주장과 크게 다르지 않다.

현실은 현재 도시 중심에 코로나19가 크게 집중되면서 ‘도시 우월주의자들’에 의해 촉진된 고밀도의 대도시는 이전에 누렸던 광택을 잃고 있다는 데 있다. 몇몇 추정에 따르면, 대도시의 사망률은 고밀도 교외 인구의 2배 이상, 저밀도 도시보다 거의 4배 더 높고, 작은 대도시 및 농촌 지역과의 격차도 이보다 훨씬 더 큰 것으로 나타났다.

인구학자 웬델 콕스(Wendell Cox)가 ‘노출 밀도 (exposure density)’로 부르는 지역에서 팬데믹은 가장 격렬하게 일어났다. 뉴욕의 한 자치구에서 일어난 최악의 사례를 보면, 이 패턴은 붐비는 아파트에서 생활하고, 사람들로 꽉 찬 거리를 걷고, 지하철에서 서로 밀착하고, 혼잡한 직업 현장에 출근할 수 밖에 없는 상황으로, 팬데믹 사태를 더욱 악화시키고 있다. 이로 인해 텍사스, 캘리포니아, 플로리다에 속한, 크지만 상대적으로 밀도가 낮은 도시 지역이 뉴욕보다 훨씬 낮은 감염률과 사망률을 경험한 이유를 설명할 수 있다.

인생의 다른 많은 측면과 마찬가지로, 코로나19 위기는 대부분의 사람들이 고려하지 않았던 위험과 기회를 최전방으로 가져왔다. 최근 해리스 폴(Harris poll) 조사에 따르면 도시 거주자의 약 40%가 덜 혼잡한 곳으로 이주하는 것을 고려하고 있다. 미 부동산협회(National Association of Realtors)에 따르면, 코로나19가 시작된 이후 더 많은 사람들이 마당이나 작업 공간을 갖춘 단독 주택을 찾고 있다.

도시 우월주의자들의 계산에서 중요한 구성 요소인 대중교통은 특히 더 바람직하지 않은 것이 된 것 같다. 팬데믹이 발생하기 전부터 이미 전국적으로 줄거나 정체되어있는 대중교통은 특히 팬데믹으로 인한 재택근무로 인해 더 큰 타격을 입었다. 여론기관 갤럽에 따르면, 현재 집에서 일하는 사람들의 60%가 가까운 미래에도 계속 이러한 근무 형태를 선호하는 것으로 나타났다.

이러한 결과는 앞으로 더 가속화될 전망이다. 뉴욕이 테러 공격을 받았던 2001년과 대조적으로, 이 도시는 현재 인구를 잃고 이주율 급등을 겪고 있다. 시카고와 로스앤젤레스의 또 다른 대도시권의 중심 도시에서도 동일한 현상이 발생하고 있다.

점점 더 늘어나고 있는 이러한 이주 경향은 사람들이 오스틴, 댈러스, 올랜도, 내쉬빌과 같은 햇볕이 잘 드는 도시를 선호한다는 것이다. 그리고 최근에는 미국인들이 더 작은 도시로 이동하고 있다. 웬델 콕스에 따르면, 미국 내 이주에서 가장 빠르게 성장하는 양상은 1백만 명 이하의 도시로 이주하는 것이다. 적어도 지금까지 뉴욕을 제외하고는 거의 모든 지역에서 인구 증가율을 보인 곳은 이러한 교외 지역들이었다.

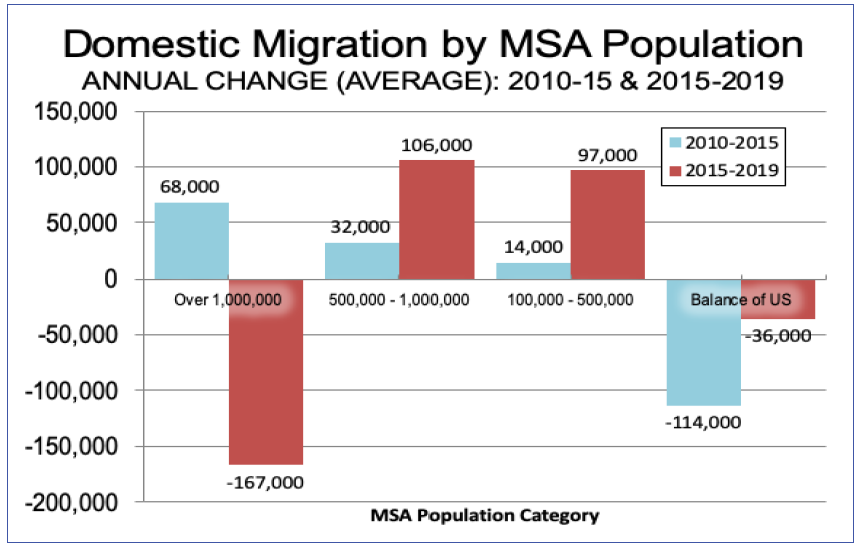

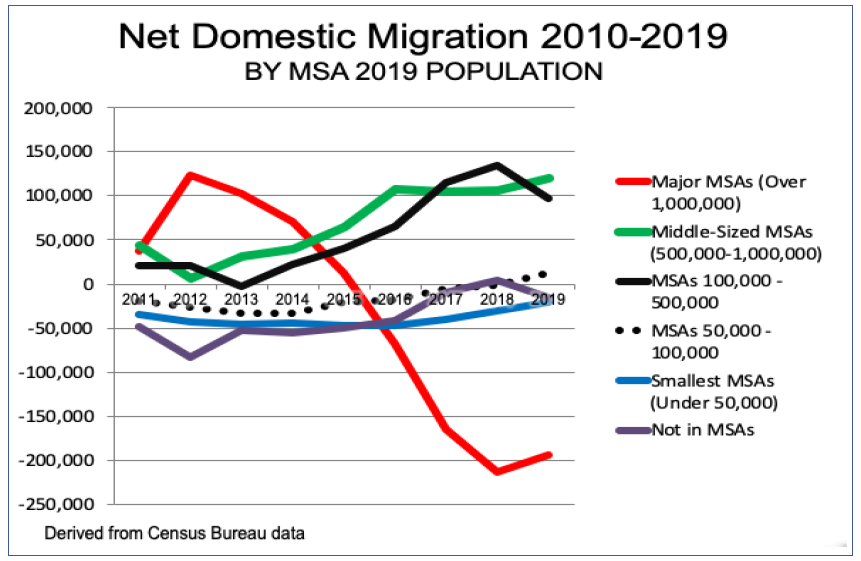

새로운 데이터에 따르면 인구 1백만 명 이상의 MSAs(metropolitan statistical areas, 대도시권)는 2010∼2015년에는 연평균 68,000명이 더 유입되었지만, 2015∼2019년에는 연평균 167,000명이 더 유출되면서 연간 순 유입률 급감을 겪고 있다. 웬델 콕스는 최근 이러한 주요 대도시권 내에서 교외 소형 대도시나 카운티로의 이주가 크게 증가했다고 밝혔다.

가장 강렬한 변화는 50만∼100만 명의 인구를 가진 MSAs에서 주로 일어났다. 10만∼50만 명의 인구를 가진 MSAs도 거의 마찬가지였다. 이 두 범주에서 2013년 이후 순 인구 유입을 경험하고 있다.

수년 동안 주민을 잃었던 5만∼10만 명 인구의 MSAs는 순 인구 유입이 개선되기 시작했다. 5만 명 이하의 MSAs와 이러한 MSAs 외부는 여전히 ??약간의 유출을 겪고 있지만 10년 전보다는 훨씬 나은 상황이다. 이와 같은 가장 작은 규모의 MSAs는 대규모 MSAs보다 순 인구 유입에 있어 전체적으로 수십 만 명을 흡수하고 있다.

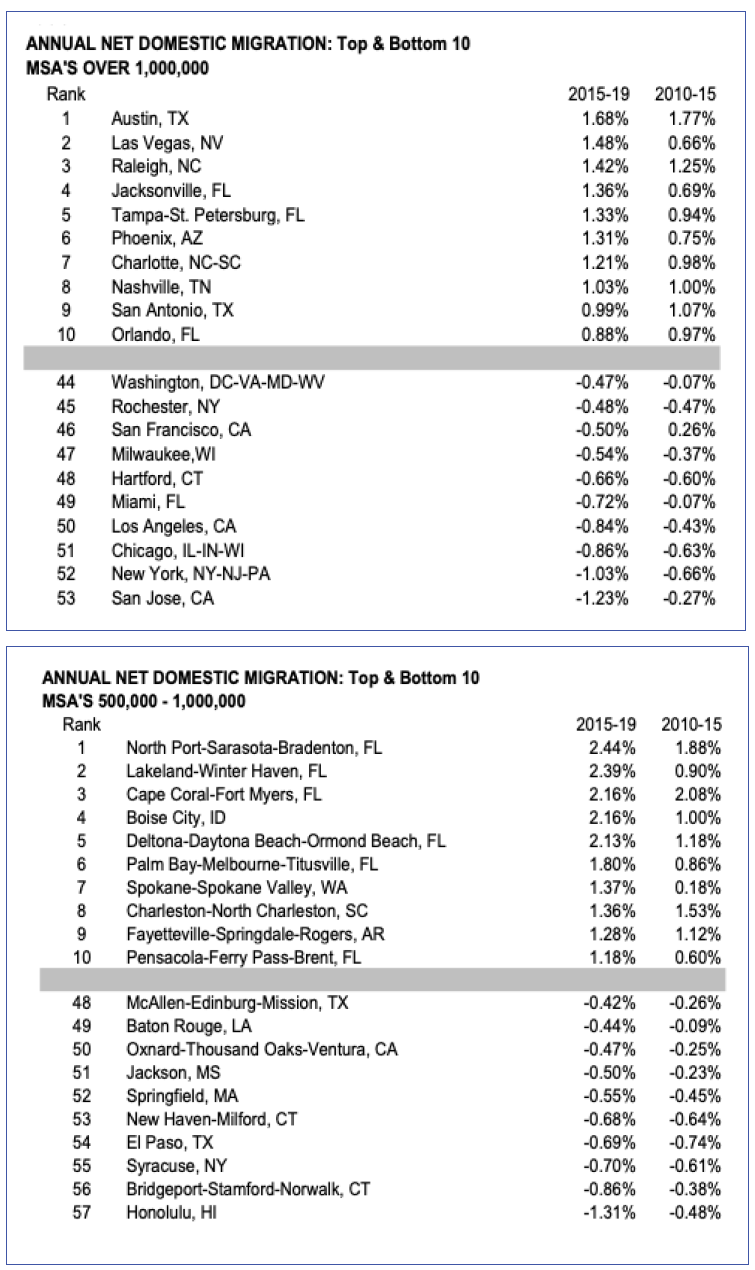

미국 내 총 926개의 MSA 중, 2015년부터 2019년까지 순 유입 인구 10위권에 50만 명 이상의 인구를 가진 곳은 없다. 그리고 10위권 MSA 모두 남부와 서부에 위치해있다.

1백만 명 이상의 인구를 가진 MSA 중, 오스틴은 2015년부터 2019년까지 매년 1.68%로 가장 강력한 순 유입률을 계속 유지하고 있다. 상위 10개 MSA 중 2개를 제외한 나머지는 모두 서부의 라스베이거스와 피닉스와 함께 남부에 위치해 있다. 특히 상위 10위권은 2010∼2015년에 비해 2015∼2019년에 더 높은 연간 유입률을 보였다. 이와 대조적으로, 하위 10위권은 2010∼2015 년에 비해 2015∼2019년 사이에 순 유출이 더 컸다.

중요한 것은 산호세, 뉴욕, 시카고, 로스앤젤레스, 마이애미에서 가장 큰 유출이 일어났다는 점이다. 이는 미 인구조사국에 의해 정의된 5대 주요 도시 지역인 로스앤젤레스, 샌프란시스코, 산호세, 뉴욕, 마이애미가 이러한 하위 10개에 속한다는 것을 의미한다.

.png)

특히, 50만∼1백만 명의 인구를 보유한 MSA 중 6개 리딩 지역의 5개가 플로리다에 있다. 바로 노스 포트-새러소타(North Port-Sarasota), 레이크랜드(Lakeland), 케이프 코럴(Cape Coral), 델토나 데이토나 비치(Deltona-Daytona Beach), 멜번(Melbourne)이다. 이 모든 곳들이 저렴한 세금, 합리적인 주택비용, 매력적인 은퇴 거주지라는 이점을 갖고 있다.

플로리다 이외의 지역에서 빠르게 성장하는 중간 규모의 MSA인 보이시(Boise), 스포캔(Spokane), 페이엣빌(Fayetteville, AR), 찰스턴(Charleston, SC)은 지속적인 성장을 위해 경제 여건을 다각화했다. 두 곳은 특히 강력한 상업 기반을 보유하고 있으며, 페이엣빌은 세계 최대 소매업체 월마트의 본사이며 찰스턴은 거대한 보잉 조립 공장을 보유하고 있다. 중요한 것은 상위 10개 중 9개가 2010∼2015년보다 2015∼2019년에 연간 순 유입률이 더 높았다는 점이다.

반대로, 하위 10대 중소 규모 MSA 중 9개는 2010∼2015년보다 2015∼2019년에 더 큰 인구 유출을 경험했다. 가장 큰 손실을 입은 곳은 호놀룰루(Honolulu), 브리지포트-스탬포드(Bridgeport-Stamford), 시러큐스(Syracuse), 엘패소(El Paso), 뉴 헤이븐(New Haven)이었다.

그렇다면 이보다 더 작은 MSA는 어떠할까?

10만∼50만의 인구 보유 범주 중 상위 MSA는 플로리다의 더 빌리지(The Villages), 푼타 고르다(Punta Gorda), 호모사사 스프링스(Homosassa Springs), 사우스 캐롤라이나의 머틀 비치(Myrtle Beach, SC), 유타의 세인트 조지(St. George)와 같은 대부분 강력한 은퇴 거주지이다. 반면, 5만에서 10만 명 인구 보유 범주 중 상위 지역은 주로 은퇴 거주지는 아니다. 상위 10개 중 8개는 보다 큰 MSA와 통근 거리 내 위치해있다. 예를 들어, 가장 큰 인구 유입을 보인 곳은 애틀란타 부근의 제퍼슨(Jefferson), 댈러스 포트워스(Dallas-Fort Worth) 부근의 그랜버리(Granbury), 리노(Reno) 부근의 펀리(Fernley), 시애틀 부근의 셀튼(Shelton)이다. 유타의 더 시티(Cedar City)와 조지아의 스테이츠버로(Statesboro)만이 보다 큰 MSA와 통근 거리 내에 위치해 있지 않다. 특히, 5만에서 10만 명 인구 보유 카테고리에서 상위 10개 MSA 중 9개가 2010∼2015년보다 2015∼2019년에 연간 순 유입이 더 높았다.

퍼시픽 노스웨스트(The Pacific Northwest)는 가장 작은 MSA 상위 10개 중 6개를 보유한 5만 명 미만의 가장 빠르게 성장하는 MSA를 갖고 있다.

이러한 사실들은 우리에게 무엇을 말하는 것일까?

코로나19 위기 이전에도 가장 큰 대도시권의 MSA에서 보다 작은 MSA 혹은 MSA 외곽 지역으로 인구가 이동하는 전례가 없었는 ‘패턴 전환’이 있었다. 최근에 이르러 바이러스와 관련된 지역 폐쇄로 인해 재택근무에 대한 관심이 높아지면서 미국 내 인구 분산이 가속화되었다. 그리고 이는 국가 경제, 사회, 정치 역학에 앞으로 더 큰 변화가 일어날 것을 예고하고 있다.

이러한 패턴 전환에 따라 우리는 향후 다음과 같은 예측을 내려 본다.

첫째, 향후 5년 동안, 실리콘 밸리, 시애틀, 뉴욕과 같은 고비용 기술 허브는 인재들의 대규모 유출을 경험할 것이다.

샌프란시스코 베이 지역의 수천 명의 기술직 종사자들에 ??대한 최근 조사에 따르면, 이들 중 3분의 2가 자택에서 영구적으로 일할 수 있는 옵션이 주어지면 이 지역을 떠날 것을 고려하는 것으로 나타났다. 이 조사는 베이 지역의 2,800명과 그 외 다른 지역의 1,600명을 포함해 4,400명의 기술직 종사자들에게 원격 근무에 대한 생각과 그것이 거주지 선택에 어떤 영향을 미치는지를 묻는 것이었다. 코로나19로 인해 전 세계 기업들은 갑자기 원격 근무로 대응했다. 이로 인해 기술 종사자들은 높은 생활비와 임대료, 끔찍한 교통 상황에 대해 점점 더 의문을 갖게 되었다. 또한 팬데믹으로 인해 사무실, 상점, 바 및 기타 편의 시설이 기한없이 문을 닫으면서 많은 기술직 종사자들은 이 지역에 머무를 이유가 없어 떠날 것을 고려하고 있다. 자택에서 근무할 수 있는 옵션이 주어지는 경우, 이주를 생각할 것인지 묻자 응답자 중 34%만이 ‘아니오’라고 대답했고, 18%는 대도시를 떠나되 캘리포니아에는 머무르는 것을 고려한다고 응답했고, 35.7%는 미국의 다른 지역으로 옮기는 것을 고려한다고 답했다. 16% 미만은 국외로 이사하는 것을 고려한다고 응답했다. 시애틀과 뉴욕, 다른 두 개의 고비용 대도시 지역과 기술 산업 허브에서도 비슷한 결과가 나왔다. 응답자의 69.5%와 62.3%가 도시를 떠날 것을 고려할 것이라고 답했다.

둘째, 대부분의 사람들에게 더 거주하기 힘든 곳이 되더라도, 캘리포니아는 그들만의 고밀도 도시화를 계속 추진할 것이다.

캘리포니아는 인구가 다른 주로 이주하면서 2018년에 18만 명, 2017년에 13만 명의 유출을 경험했고, 2019년은 유출은 아마도 더 증가했을 것이다. “지구를 구한다”는 명복 하의 대도시권 중심 도시 고밀도 정책은 각종 비용을 증가시키고, 거주 적합성 위기를 일으켜왔다. 이는 캘리포니아를 인구학자 조엘 코트킨(Joel Kotkin)이 말하는 ‘21 세기 봉건 국가’로 만드는 것이다. 로스앤젤레스 1 베드룸 아파트의 월 평균 임대료는 2,300달러이고, 샌프란시스코에서는 3,400달러가 넘는다. 한편, 1 베드룸 기준의 임대 가격은 라스베이거스에서는 925달러, 피닉스에서는 945달러이다. 당연히 2015∼2017년까지 캘리포니아 주민들에게 가장 인기있는 이주지는 워싱턴, 텍사스, 네바다로, 이곳은 소득세가 없거나 캘리포니아에 비해 저렴하다. 그러나 이렇게 심각한 인구 변화에 직면하고 있음에도 기존 ‘기술 및 금융 허브’는 고밀도화를 포기하지 않을 것으로 보인다.

셋째, 미국 내 더 많은 지역으로 기술 인재들을 분산시키는 것이 미국 전역의 주 및 지방 경제에 활기를 불어 넣을 것이다.

미 전역으로 ‘기술 인재들와 그에 따른 부문들’이 확산되면 벤처 자본가와 기업가는 투자 대비 더 많은 기회를 확보할 수 있고, 더 많은 사람들이 새로운 아이디어에 참여하고 기여할 수 있다. 그 결과 더 많은 사람들에게 풍요가 분배되고, 보다 포괄적이고 생산적인 혁신이 이루어질 확률이 높다.

넷째, 코로나19 위기 이후에 발생하는 본격적인 인구 분산이 가장 크고 밀도가 높은 대도시의 힘과 영향력을 감소시킬 것이다.

푸젓 사운드(Puget Sound)와 샌프란시스코 베이(San Francisco Bay) 지역을 제외하고 고급 일자리 창출 현상은 오스틴(Austin) 및 롤리(Raleigh)와 같은 소규모 도시로 이동하고 있다. 더불어 대부분의 미국 대도시들은 사회 정책에 있어 바람직스럽지 않은 일련의 논쟁을 야기하고 있다. 예를 들어 시애틀과 뉴욕과 같은 진보 성향의 주 정부는 새로운 세금과 규제를 계속 만들어 스타트업 기업들이 일으킬 새로운 ? 혹은 앞으로 발생할 - 비즈니스를 밖으로 밀어내는 경향이 있다.

다섯째, 현재 코로나19로 더욱 가속화된 이러한 인구통계학적 트렌드가 미국의 정치적 미래를 크게 바꿔 놓을 것이다.

우선 의회 구성의 변화를 살펴보자. 1950년에 북동부에는 115명의 의원이 있었지만 지금은 78명이 있으며 앞으로 좌석을 더 잃게 될 것이다. 전통적으로 민주당이 강세를 보여 온 캘리포니아는 한 세기 넘게 많은 좌석을 확보하고 있었지만 이제는 전국 평균 이하의 성장으로 인구가 유출되어 기존 좌석을 보존하기 힘들 가능성이 높다. 한편, 플로리다는 좌석이 2개 늘어나고, 애리조나, 몬태나, 노스 캐롤라이나, 콜로라도, 오레곤은 좌석을 1개 더 늘릴 수 있다. 이러한 변화는 크지 않은 것 같지만, 전체적인 의원 구성과 지지 정당의 이해관계를 대입하면 정치적 변화의 단초가 될 수 있다. 어떤 정당에게 이익이 될 것인지를 향후 지켜봐야 할 것이다.

* *

?

References List :

1. The Hill. May 17, 2020. Joel Kotkin. The new geography of America, post-coronavirus.

https://thehill.com/opinion/campaign/498198-the-new-geography-of-america-post-coronavirus

2. Business Insider. May 20, 2020. Rob Price. A survey of thousands of SF Bay Area techies found that 2 out of 3 would consider leaving if they could permanently work remotely.

https://www.businessinsider.com/two-thirds-tech-workers-leaving-sf-bay-area-wfh-blind-2020-5

3. The Daily Caller. May 23, 2020. Chris Whitech. Silicon Valley Giants Are Allowing Staff to Work Remote Permanently. Will Their Workers Flood into Red States?

https://dailycaller.com/2020/05/23/facebook-twitter-employees-work-remotely-leave-california/

4. com. December 19, 2019. Ryan Streeter. Place and the pursuit of happiness, upward mobility, and the American Dream.

https://www.aei.org/articles/place-and-the-pursuit-of-happiness/

5. com. March 25, 2020. Wendell Cox. DOMESTIC MIGRATION TO DISPERSION ACCELERATES (EVEN BEFORE COVID).

https://www.newgeography.com/content/006648-domestic-migration-dispersion-accelerates-even-covid

6. com. March 25, 2020. Joel Kotkin The Coming Age of Dispersion.

http://www.newgeography.com/content/006588-the-coming-age-dispersion

7. com. June 7, 2019. Ryan Streeter. Dynamism for the working class.

https://www.aei.org/articles/dynamism-working-class/

|  |

The Rise of the New American Community

For decades the Trends editors have highlighted the absurdity of the great urbanization trend. So-called experts insisted on conflating the mass flight from rural poverty in the developing world with the continued growth of certain dense urban centers in the OECD countries. Much of the confusion arises from the biases of analysts in parsing the data. For instance, as explained in prior Trends issues the often-quoted assertion that “dense urban areas are exceptionally productive” in economic terms, turns out to be untrue when the data is accurately parsed.

Nevertheless, for a generation, a procession of pundits, public relations agents, and real estate speculators have promoted the notion that our future lay in dense - and politically deep-blue - urban centers, largely on the coasts. In fact, in the midst of the financial crisis just a decade ago, suburbia’s future seemed perilous, with experts claiming that many suburban census tracks were about to become “the next slums.” Specifically, the head of President Obama’s Department of Housing and Urban Development proclaimed that “sprawl” was now doomed and people were “moving back into central cities.” Of course, that “wisdom” came from the same administration that told us “you can’t drill your way to energy independence” and “those U.S. manufacturing jobs are never coming back.”

Notably, that idea was always overwrought with enthusiasm. But now, with the COVID-19 pandemic heavily concentrated in these urban centers, the case for forced densification promoted by “urban supremacists” has lost a lot of its former luster. Why? Because, by some estimates, the death rate in large urban counties has been well over twice those of high-density suburbs, nearly four times higher than lower-density ones, with even larger gaps with smaller metros and rural areas.

The pandemic has been toughest on those areas that suffer what demographer Wendell Cox called “exposure density.” In the worst case, which is in New York’s outer boroughs, this pattern is exacerbated by living in crowded apartments, walking packed streets, traveling cheek-to-jowl in the subway, and then being forced into a crowded workplace. This could explain why sprawling, large, and relatively less-dense urban areas in Texas, California, and Florida - each with its own pockets of poverty - have also experienced far lower infection and fatality rates than New York.

As in so many other aspects of life, the COVID19 crisis has brought to the forefront both threats and opportunities which most people had never considered. And those new insights have combined with well-known concerns to make people rethink many aspects of life. A recent Harris poll suggests that nearly 40% of urban residents are considering a move to a less crowded place. And according to the National Association of Realtors, since the pandemic began, more people are seeking out single-family houses with such things as yards and workspaces.

Mass transit, a critical component in the urban supremacists’ calculation, seems to be particularly out of favor. Already declining or stagnating around the country before the pandemic, mass transit has taken a particularly nasty hit, with more people than ever looking for alternatives, especially telecommuting. According to Gallup, 60% of people now working from home express a preference to continue to do so for the foreseeable future.

These findings don’t represent a break with the past but rather an acceleration of pre-existing trends. In contrast to 2001, when New York was last under assault, the city is now losing population and suffering mounting out-migration. The same dynamics are already being seen in our two other large metropolitan centers, Chicago and Los Angeles.

Increasingly, migration trends favor sprawling sunbelt cities such as Austin, Dallas, Orlando, and Nashville. And more recently, Americans have been heading to even smaller cities. The fastest growth in domestic migration, notes demographer Wendell Cox, is now to cities with less than a million people, a dramatic change from just a decade ago. In virtually all areas - with the notable exception, at least so far, of New York - an increasing share of population growth has also shifted to suburban locales.

The new data shows that the metropolitan statistical areas (or MSAs) with over 1,000,000 population, have seen their annual net domestic migration plummet from an average annual gain of 68,000 from 2010 to 2015 to an annual loss of 167,000 from 2015 to 2019. Cox recently reported that within these major metropolitan areas, migration has increased strongly from the central to suburban counties. At the same time, smaller MSAs and areas outside MSAs are doing much better. Some of these are in the smallest population categories and are adjacent to the retirement communities that have attracted so many new residents, principally in Florida.

The strongest net domestic migration performance is in MSAs with 500,000 to 1,000,000 in population, and those with 100,000 to 500,000 population have done nearly as well. Both categories have experienced big gains in net domestic migration since 2013.

MSAs with from 50,000 to 100,000 population, which hemorrhaged residents for years, have improved and have begun to gain net domestic migrants.

Meanwhile, MSAs under 50,000 and areas outside MSAs are still suffering modest losses while doing much better than earlier in the decade. Both of the smallest categories are also attracting hundreds of thousands more in net domestic migrants than the largest MSAs.

Among America’s 926 MSAs, the ten leading net domestic migration leaders from 2015 to 2019 include none with populations above 500,000. And all ten are in the South or West.

Among the MSAs over 1 million, Austin continues to have the strongest net domestic migration, at 1.68% annually from 2015 to 2019. All but two of the top ten large MSAs were in the South, joined by Las Vegas and Phoenix from the West. And notably, the top 10 had higher annual gains from migration 2015-to-2019 than in 2010-to-2015. In contrast, the bottom 10 had larger net domestic migration losses in 2015-to-2019 than in 2010-2015.

Importantly, the biggest losses were in SanJose, New York, Chicago, Los Angeles, and Miami. That means the five densest major urban areas, as defined by the US Census Bureau (Los Angeles, San Francisco, San Jose, New York, and Miami) are part of this bottom ten.

Notably, five of the six leading gainers among MSAs with 500,000 to 1,000,000 people were in Florida: North Port-Sarasota, Lakeland, Cape Coral, Deltona-Daytona Beach, and Melbourne. These all benefit from low taxes, reasonable housing costs, and being attractive retirement destinations. Nine of the top ten had more annual net domestic migration than in 2010-2015.

Outsides of Florida, the fast-growing mid-sized MSAs Boise, Spokane, Fayetteville (AR) and Charleston (SC) have diversified economies that seem well-positioned for continued growth. Two have particularly strong commercial bases, Fayetteville, is headquarters for (Wal-Mart) the world’s largest retailer and Charleston has a huge Boeing Assembly plant. Importantly, nine of the top 10 had higher annual net domestic migration in 2015-to-2019 than in 2010-to-2015.

On the contrary, nine of the bottom 10 mid-sized MSAs had larger net domestic migration losses in 2015-to-2019 than in 2010-to-2015. The largest losses were in Honolulu, Bridgeport-Stamford, Syracuse, El Paso, and New Haven.

What about smaller MSAs?

The top MSAs in the 100,000 to 500,000 categories are mostly strong retirement destinations, such as The Villages, FL, Myrtle Beach, SC, Punta Gorda, FL, St. George, UT, and Homosassa Springs, FL.

On the other hand, the top domestic migration gainers in the 50,000 to 100,000 categories are not principally retirement destinations. Eight of the top ten are within commuting distance of large MSAs. For example, the largest gainers were Jefferson, GA (near Atlanta), Granbury, TX (near Dallas-Fort Worth), Fernley, NV (near Reno), and Shelton, WA (near Seattle). Only Cedar City, UT, and Statesboro, GA are not within commuting distance of a larger MSA. And notably, nine of the top 10 MSAs in the 50,000 to 100,000 category had higher annual net domestic migration in 2015-to-2019 than in 2010-to-2015.

The Pacific Northwest dominates the category of fast-growing MSAs under 50,000 people with six of the top ten positions among the smallest MSAs.

What’s this telling us?

Even prior to the COVID19 crisis there was an unprecedented switch in growth patterns from the largest metropolitan MSAs to smaller MSAs, as well as areas outside MSAs. Now, with the greater interest in working from home, triggered by virus-related lockdowns, U.S. population dispersion could accelerate further transforming the economic, social, and political dynamics of the nation.

Given this Trend, we offer the following forecasts for your consideration.

First, over at least the next five years, high-cost tech hubs like Silicon Valley, Seattle, and New York City will experience a major exodus of talent.

A recent survey of thousands of San Francisco Bay Area tech workers found that two-thirds would consider leaving the region if they were given the option to work from home permanently. The survey asked 4,400 tech workers including 2,800 in the Bay Area and 1,600 elsewhere for their thoughts on working remotely and how it would affect their choice of where to live. The pandemic has forced companies around the world to abruptly transition to an entirely remote workforce. This has made workers increasingly question whether they want to deal with the high cost of living, a major housing crisis, and terrible traffic. Furthermore, with offices, shops, bars, and other amenities off-limits because of the pandemic, many tech workers say they have no reason to stay and are considering leaving the region, and some real-estate professionals in rival regions have said theyve seen an uptick in interest. Asked whether they would "consider relocating" if, given the option to work from home as much as possible, only 34% of Bay Area respondents said no. About 18% said theyd consider moving out of the metro area but staying in California, 35.7% said theyd consider going elsewhere in the U.S., and just under 16% said theyd consider moving out of the country. Similar results were found for Seattle and New York, two other high-cost metro areas, and tech-industry hubs; there 69.5% and 62.3% of respondents respectively said theyd consider leaving the cities.

Second, California, in particular, will continue its quixotic pursuit of high-density urbanization even as it makes the state ever more unlivable for most people.

California lost 180,000 people in 2018 and 130,000 in 2017 due to state-to-state migration - and 2019 was probably worse. What’s happening? Densification policies in the name of “saving the planet” are driving costs up costs, creating livability crises, and turning California into what demographer Joel Kotkin calls “a 21st-century feudal state.” Median monthly rent for a Los Angeles one-bedroom apartment is $2,300, while it’s more than $3,400 in San Francisco. Meanwhile, the rental price for a one-bedroom unit is $925 in Las Vegas and $945 in Phoenix. Not surprisingly, the most popular re-location sites for Californians from 2015 to 2017 were Washington, Texas, and Nevada, which do not have an income tax and are inexpensive relative to California. The tech and financial hubs which face wrenching demographic change will be unwilling to abandon their commitment to densification for at least three reasons: (1) A “religious commitment” to the “green agenda,” which prevents them from addressing the evidence objectively. (2) The vested interest of home-owning voters in keeping prices extremely high. And (3) the typical unwillingness of human beings to admit that they’ve been wrong.

Third, the dispersion of tech talent to more U.S. locations will invigorate state and local economies across the U.S.

As we’ve explained in previous issues, diffusion of the “tech sector” across the country would allow venture capitalists and entrepreneurs to get more bang for their invested bucks and allow a wider range of people to “contribute their ideas. The result will be a more inclusive and productive innovation that enriches more people.

Fourth, the post-crisis dispersion of the population will diminish the power and influence of our largest and densest cities. With the exception of the Puget Sound and San Francisco Bay areas, high-end job creation has been shifting to smaller cities like Austin and Raleigh. In addition to trends we’ve discussed, most large U.S. cities are now increasingly making a series of unforced errors in social policy. Increasingly radicalized city governments - for example, in Seattle and New York - have pushed new businesses out, with new taxes and regulation. Meanwhile, other policies have created streets filled with homeless people, drug addicts, petty thieves, and even sex offenders.

Fifth, these demographic trends, now accelerated by the COVID19 crisis, will profoundly reshape our political future.

Consider the changing make-up of Congress: in 1950 the Northeast had 115 members of the House, but now it has 78, and will soon lose more. California, another blue area, was a great gainer of seats for well over a century, but it is now growing below the national average, losing population, and likely to lose a seat for the first time. Meanwhile, the red states are gaining seats as follows: Texas picks up three seats; Florida picks up two; Arizona, Montana, and North Carolina get one each. Colorado, which is purple, will add one, and Oregon is the only blue state on the list to get one. Obviously, these changes could help the GOP, but the migration of millennials out of the deep-blue areas could give Democrats hope of moving other states to the left as we’ve seen in Colorado. And,

Sixth, regardless of the actions taken by state and local government, the best days for California and New York City real state are behind us.

Like tulip bulbs and dot-com stocks, prices have become decoupled from long-term intrinsic value. Selling now and investing in equities probably makes the most sense. Florida and Texas real estate may also make sense depending on the leverage used.

References

1. The Hill. May 17, 2020. Joel Kotkin. The new geography of America, post-coronavirus.

https://thehill.com/opinion/campaign/498198-the-new-geography-of-america-post-coronavirus

2. Business Insider. May 20, 2020. Rob Price. A survey of thousands of SF Bay Area techies found that 2 out of 3 would consider leaving if they could permanently work remotely.

https://www.businessinsider.com/two-thirds-tech-workers-leaving-sf-bay-area-wfh-blind-2020-5

3. The Daily Caller. May 23, 2020. Chris Whitech. Silicon Valley Giants Are Allowing Staff to Work Remote Permanently. Will Their Workers Flood into Red States?

https://dailycaller.com/2020/05/23/facebook-twitter-employees-work-remotely-leave-california/

4. com. December 19, 2019. Ryan Streeter. Place and the pursuit of happiness, upward mobility, and the American Dream.

https://www.aei.org/articles/place-and-the-pursuit-of-happiness/

5. com. March 25, 2020. Wendell Cox. DOMESTIC MIGRATION TO DISPERSION ACCELERATES (EVEN BEFORE COVID).

https://www.newgeography.com/content/006648-domestic-migration-dispersion-accelerates-even-covid

6. com. March 25, 2020. Joel Kotkin The Coming Age of Dispersion.

http://www.newgeography.com/content/006588-the-coming-age-dispersion

7. com. June 7, 2019. Ryan Streeter. Dynamism for the working class.

https://www.aei.org/articles/dynamism-working-class/