|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

| 글로벌 트렌드 | 내서재담기 |

|

|  |

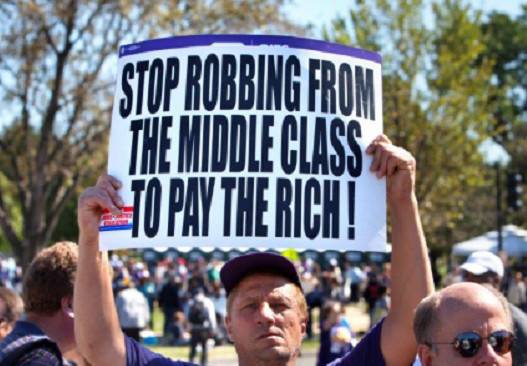

한때 미국의 근간을 지탱하던 중산층 붕괴로 인해 양극화는 심화되고 사회안전망도 흔들리고 있다. 더 이상 ‘아메리칸 드림’이란 말이 통하지 않는 세상이 된 것이다. 이러한 중산층의 위기는 어디에서 비롯되었으며, 그 결과는 어떤 방향으로 나아갈 것인가?

단언하건대 향후 10년 내 미국이 직면할 가장 큰 위기는 아마도 전통적 중산층의 붕괴가 될 것이다. 전체 인구의 60∼80%를 차지했던 이 계층은 대량생산 시대부터 출발해 미국 경제의 주도 세력이자 동력이었다. 다른 몇몇 나라들도 그랬지만, 19세기 후반부터 미국 문화를 정의할 때 사용된 매스미디어, 대중소비, 상대적으로 균질한 사회적 가치 등은 모두 중산층의 특징이기도 했다.

대부분 이들은 핵가족에 주택, 차량, 전화, 텔레비전을 소유하고, 몇 개의 텔레비전 네트워크를 시청했으며, 대개 공립학교를 다녔다. 명목상으로는 거의 기독교인 혹은 유대인이었으며, 기업과 정부를 신뢰했고, 자신들보다는 자녀들의 삶이 더 나아질 것이라 생각했다. 이러한 인식은 일반적으로 고등학교만 졸업하면 위와 같은 삶의 욕구를 충족해 줄 평생 직업을 얻을 수 있는 기회를 충분히 제공하는 경제 시스템에 대한 믿음에 기초하고 있었다. 은퇴 뒤에도 든든한 사회안전망과 함께 이런 이상적인 중산층의 삶은 이민자와 세계 각지의 사람들이 부러워하는 ‘아메리칸 드림’이 되었다.

그러나 불행하게도 대량생산의 물결이 멈추고 그 자리를 디지털 혁명에 내주면서, 중산층의 이상은 낡은 깃발처럼 휘둘리기 시작했다. 그리고 이미 디지털 혁명의 여명이 밝아온 지 40여 년이 지난 지금도 여러 트렌드의 교차 속에서 그 방황은 계속되고 있다. 분명한 것은 미국 중산층이 여전히 새로운 기회를 찾고 있지만, 실제 실현 가능성에 대해서는 점점 회의적으로 변해가고 있다는 점이다.

앞으로 어떤 일이 일어날지 살펴보려면, 우선 20세기 미국이 역사적으로 얼마나 독특했는지, 왜 미래가 그와는 달라질지를 이해해야 한다. 전 세계가 부러워했던 20세기 미국 중산층의 풍족함을 이룬 요건들을 살펴보기로 하자.

우선 미국은 항구, 강, 물리적 장벽이 거의 없는 평야 등 운송 환경뿐 아니라 군사적 안전성, 농업 생산성, 풍부한 자원(철강, 석탄, 석유 등)이라는 측면에서 보면 그야말로 축복받은 나라다. 외세 침략이나 천연자원 부족에 대해 걱정할 필요가 없었기 때문에 자체적으로 자유롭게 경제를 발전시킬 수 있었다. 영국에서 발현된 제1차 산업혁명을 가능하게 한 기술과 기업적 가치가 미국에 그대로 유입되었다. 또 비록 현재는 인종과 문화 사이의 갈등이 존재하지만, 최초 미국이라는 국가의 탄생에는 평등 문화가 그 기반을 이루고 있었다. 이러한 배경 아래 철도 혁명과 철강 혁명이 대량생산의 기초를 마련했다. 거기에 더 나은 삶을 찾아 떠나온 유럽의 이민자들이 미국으로 유입되고 동화됐다. 비약적으로 증가한 농업 생산성과 더불어, 이러한 이민은 어느 정도 숙련된 노동자를 엄청나게 공급하여 대량생산 패러다임을 이끌었다.

둘째, 대량생산 패러다임은 대량생산 시대가 시작된 1908년 당시 미국 사회에 이상적으로도 부합했다. 비록 고등학교를 마친 사람들이 그리 많지는 않았지만, 당시 미국인들은 읽고 쓸 줄 아는 사람의 비율이 세계에서 가장 높았다. 천연자원은 넘쳤고 철도와 운하는 저렴한 수송비를 보장했다. 규모의 경제가 중요시되었고 농업 자동화 덕분에 새 공장에 노동자들이 공급될 수 있었다. 이 모든 것들이 이상적인 자기 강화형 순환구조를 만들어냈다. 중간 정도의 숙련도를 갖춘 노동자들이 증가하여 저렴하고 우수한 제품을 생산했고, 이 제품들은 다시 효율적인 유통 채널을 통해 매스미디어에 의해 구매욕이 증진된 노동자들에게 팔려나갔다.

셋째, 대중소비 시장은 규모의 경제, 취향의 규격화, 수요 증가에 맞출 수 있는 강력한 생산성 등 여러 요소에 의존한다. 이 요소들의 조화가 대공황Great Depression 시기에는 비록 깨졌지만, 2차 세계대전 이후 다시 전성기를 이뤘다. 사회 혼란과 전쟁 덕에 방위산업에 자본이 집중됐고, 대량생산 모델을 최적으로 지원할 수 있는 사회 제도가 만들어졌다. 여기에는 소비자 금융, 효과적인 은행 규제, 중산층을 위한 사회안전망 등이 포함되는데, 사회보장연금제도, 재해보험, 노인의료보험 등으로 이어졌다. 더욱 중요한 점은 전쟁 기간 동안 유럽과 아시아에서 발생한 생산 시설 파괴로 인해 미국이 전 세계적으로 브랜드, 생산 시설, 유통 채널을 구축하는 역사적인 기회를 창출할 수 있었다는 것이다. 미국의 중산층 노동자들은 이 ‘경제적 제국주의’의 분위기를 만끽했으며, 이러한 호황이 사그라들 것이라고는 의심조차 하지 않았다.

넷째, 검소, 정절, 정직과 같은 중산층의 가치는 상대적으로 균질적인 사회를 형성하는 데 일조했고, 모든 사람들이 텔레비전에 그려지는 중산층의 삶과 행동을 열망하게 만들었다. 그리고 이렇게 표준화된 이상理想이 대량생산되는 제품과 서비스를 소비하도록 부추긴 것이다.

그러나 이 모델은 1960년대 후반부터 1970년대 초반에 한계에 직면하기 시작했다. 물론 70년대는 대량생산 혁명의 안정기였지만, 동시에 디지털 혁명이 탄생하고 있었다. 80~90년대에 퍼스널 컴퓨터와 인터넷이 등장했지만 대량생산 혁명 당시 만들어진 제도들은 그다지 변하지 않았다. 미국 중산층 노동자들은 50~60년대, 심지어 70년대까지도 예외적인 상황에 의한 이익을 누렸지만, 기존 경제구조와 새로운 디지털 혁명의 수요가 불일치하면서 발생하는 고통은 점점 더 커지고 있었다.

이것이 가장 잘 드러나는 부분이 노동시장에서 심화되는 양극화 현상이다. 중간 정도의 숙련도를 가진 노동자에 비해 고숙련, 저숙련 노동자가 증가하는 현상이 지난 20년에 걸쳐 명확하게 나타났다. 1980년대 미국 노동시장은 양극화가 그리 심하지 않았다. 숙련도가 낮아도 되는 일자리가 숙련도가 높은 노동자를 필요로 하는 일자리로 대체됐지만, 중간 숙련도 일자리에는 큰 변화가 없었다. 그러나 약 25년 전인 1990년대 초반부터 양극화가 시작되었고 2000년대에 심화되었다.

미국 ‘댈러스 연방준비은행’의 보고서에서 경제학자 안톤 체레무킨Anton Cheremukhin은 경제적 진화가 어떻게 이러한 양극화를 주도했는지 설명했다.

“미국 내 고용이 점차 양극화되면서 최고 임금 또는 최저 임금 일자리에 대한 쏠림 현상이 심해지고 있다. 중간 숙련도 일자리와 관련된 미국 내 시장 변화가 노동시장 양극화를 재촉하는 양상이다. 숙련 수준에 따른 일자리 분포는 1980년 이후 극적으로 변화해왔다. 중간 정도의 숙련도가 필요한 일자리는 사라지고 있는 한편, 숙련도가 필요 없거나 고숙련 노동자를 요구하는 일자리에 대한 수요는 팽창했다. 중간 숙련도의 일자리가 줄어드는 현상은 노동조합의 쇠퇴 같은 노동시장 제도의 변화에 의한 것이 아니다. 오히려 반복적 업무의 자동화 확대, 숙련된 노동자들의 상대적 품귀, 국외로의 일자리 재편성으로 인해 일자리의 양 극단이 상대적으로 커진 것이다. 숙련도가 낮고 저임금에 단순 노동을 하는 사람들이, 숙련도가 높고 고임금에 단순하지 않은 문제 해결 위주의 일을 하는 고급 노동자와 함께 늘어나고 있다. 1990~1991년, 2001년, 2008~2009년의 침체 시기와 마찬가지로 단순 업무에 대한 수요의 감소는 예외적인 현상을 보인다. 그 이전의 쇠퇴기들과는 달리, 이 시기 이후 찾아온 경기 팽창기에도 중간 숙련도 일자리는 회복되지 않았다.”

실제로 어떤 일이 일어나고 있는지 이해하려면, 사람들이 수행하는 일의 본질을 면밀하게 살펴야 한다. 정부가 일자리에 대한 데이터를 수집할 때 직업은 다음의 4가지로 분류된다.

1. 인지적 비반복형 직업 - 보통 고숙련 일자리를 말하며, 문제 해결, 직관, 설득 등 추상적인 업무를 진행하는 경우가 많다. 대개 대학 학위를 요구한다.

2. 매뉴얼 비반복형 직업 - 보통 저숙련 일자리를 의미한다. 매뉴얼을 따라하면 되는 일로, 상황 적응력, 시각적·언어적 인식력, 대인관계 능력이 필요하다. 대부분 고등학교 졸업장이 필요 없다.

3. 인지적 반복형 직업 - 중숙련 일자리를 말한다. 정확하고 잘 이해되는 절차를 수행할 능력을 필요로 하는데, 이런 직업의 경우 컴퓨터로도 수행이 가능하다. 대개 고등학교 졸업 이상의 학력을 요구한다.

4. 매뉴얼 반복형 직업 - 저숙련 일자리로, 정확하고 잘 이해되는 절차를 수행하는 능력이 필요한 일이지만 컴퓨터로는 수행하기 어려운 일이다. 이 직업 역시 고등학교 졸업장이 필요 없다.

반복형 직업은 1981년에는 미국 고용시장의 58%를 차지했으나 2011년에 44%로 줄었다. 반면 같은 기간 두 유형의 비반복형 일자리는 모두 늘었다. 반복형 직업에서 밀려난 14% 중 10%는 급여가 높은 고숙련(인지 비반복형) 직업으로 대체되었고, 나머지 4%는 저숙련(매뉴얼 비반복형) 직업이 차지했다.

인지 반복형 직업 중 가장 급격히 줄어든 일자리는 주로 행정 지원이나 판매직에 집중되었다. 빠르게 사라지는 직업군에는 서기, 은행 창구 직원, 출납원, 텔레마케터, 권리분석사, 경리담당자, 보험업자, 여행사 직원, 기술자 등이 있다. 매뉴얼 반복형 직업 중 쇠퇴하고 있는 것은 우편배달부, 운전수, 요리사, 도장조각가 등이 있다.

그럼 이러한 변화의 배경은 무엇이며, 대량생산 시대와 디지털 시대에 맞는 제도적 특성이 서로 각각 달라 생기는 문제와는 어떠한 관련이 있는가?

첫째, 조직화된 노동력, 즉 노동조합이 대량생산 시대의 미국 노동시장을 정의하는 주요 제도였다. 특히 제조업과 공공업무 등 조직력이 강한 분야에서 두드러졌는데, 이 두 영역에서 미국은 경쟁력을 잃어왔다. 오늘날 외국 자동차 회사들은 노조가 없는 미국 현지의 공장에서 자동차를 생산해 미국 시장에 공급하고 있다. 쇠락한 미국 내 제조업체가 이들과 경쟁할 수 있게 하기 위해 마지못해 노동조합이 근무조건을 다소 양보해 주고 있는 형편이다. 노동조합이 있는 회사들의 경우 반복 업무를 해외에 맡겨 처리하는 경향이 점점 일반화되고 있다.

둘째, 중간 숙련도가 필요한 일자리, 특히 인지적 반복형 직업이 사라지면서 남성보다 여성들이 더 큰 피해를 입었다. 그러나 여성은 또한 자신의 능력을 향상시키고 급여가 더 좋은 일자리를 찾는 일에도 더 적극적이다. 이에 비해 중숙련 일자리, 대개 매뉴얼 비반복형 직업을 잃은 남성들의 절반은 급여가 더 낮은 일자리에 정착해야 했다. 근래 들어 여성의 교육 참여율이 높아진 것이 이러한 차이를 나타내는 주된 이유가 됐다.

셋째, 대량생산 시대의 제도와 중간 숙련도의 중산층 직업을 가질 인력을 지원하는 데 필요한 제도 간의 차이가 벌어지는 이유는 아마 이것일 것이다. 대량생산 모델에서는 매뉴얼 비반복형 노동자와 인지적 반복형 노동자가 많이 필요했지만, 이 두 유형의 직업군은 빠르게 자동화되고 있다는 사실 말이다.

오늘날 인지적 비반복형 직업을 구하려면 대학 또는 대학원 학위가 필요하다. 1980년대 초반에는 고등학교만 나와도 더 이상 직업에 소중한 학위를 더 필요로 하는 사람이 너무 적었기 때문에, 고등학교 졸업자에 비해 대학 학위를 가진 노동자의 증가세가 아주 완만했다. 그 결과 대학 학위가 갖는 프리미엄이 가파르게 상승하여 1982년에는 대학 졸업자의 급여가 고등학교 졸업자에 비해 10% 정도 높았지만, 2008년에는 무려 두 배가 됐다. 수많은 사람들이 고임금 직업을 찾지 못하고 저임금 일자리에 내몰리는 이유 중 하나는 상대적으로 교육 수준이 낮기 때문이다.

넷째, 중산층의 몰락을 이끄는 마지막 요인은, 일자리를 잃은 중간 숙련도 노동자들이 대개 임금이 더 적은 매뉴얼 반복형 직업으로 전락했다는 점이다. 또한 2000년 이후 창출된 새로운 일자리는 거의 이민자들로 채워졌다. 인도나 중국에서 이민 온 박사급 인력들은 인지적 비반복형 직업의 부족분을 채웠다. 또한 멕시코에서 온 정원사, 니카라과에서 온 웨이터 등이 미국 중산층들의 임금을 억제하는 데 일조하기도 했다.

이러한 사실과 현실을 볼 때 우리는 앞으로 다음과 같이 예측해본다.

첫째, 노동조합은 앞으로 10년 이내에 대부분 의미를 상실하게 될 것이고, 취업규칙이나 교육 개혁에 대한 장벽도 허물어질 것이다.

민간 부문에서의 노동조합은 이미 대개의 영역에서 유명무실해졌지만, 공공 부문의 조합은 교육과 규제 개혁에 가장 큰 장애물로 남아 있다. 하지만 최근에는 여론과 정치권도 그들에게 등을 돌리는 추세다. 오하이오, 인디애나, 미시건, 위스콘신, 일리노이 등 노동조합으로서는 역사적 보루라고 할 수 있는 지역들도 이제는 공공 부문 노동조합의 힘을 약화시키는 정책을 추진하고 있다.

둘째, 미국 에너지 혁명과 제조업의 부활을 통해 상당수의 매뉴얼 비반복형 직업이 다음 10년 동안 창출될 것이다.

최근 원유 시장의 혼란 사태에도 에너지 붐은 한동안 지속될 것이다. 탐사, 운송, 정제의 매 과정마다 새로운 미국인의 일자리들이 만들어지고 있으며, 동시에 3D 기술과 소비시장에 대한 근접성, 경쟁력 제고로 인해 제조업에서도 부흥이 일어날 것이다.

셋째, 전개 단계에 들어선 디지털 기술-경제 혁명이 새로운 인지적 비반복형 일자리들을 창출해낼 것이다.

앞서 말한 대로 공공 부문에서 노동조합의 세력이 약해지면 매뉴얼 비반복형, 인지적 비반복형 직업에 필요한 기술에 보다 집중한 교육으로 바꿔나갈 수 있을 것이다.

넷째, 이르면 2018년, 미국은 국내 노동자를 보호하는 쪽으로 이민 정책의 기조를 바꿀 것이다.

현재의 이민 정책은 고용인과 피고용인의 니즈를 제대로 반영하지 못하고 있다. 미래의 정책은 연구자나 기업가 등 미국으로 이민을 희망하는 인력을 선별하는 형식으로 변화될 것이다. 동시에 불법 이민에 대한 방지책이 마련되고, 기존 불법 이민자들에게 대한 파악과 조치도 강력해질 것이며, 기업들은 현재 미국 산업구조에 적합한 인력만 채용할 수 있게 될 것이다. 30년 전만 해도 이러한 정책에는 엄청난 비용 손실이 뒤따라야 했지만, 기술과 구조의 발전으로 인해 이제는 정치적 의사결정만 남았을 뿐이다.

* *

References List :

1. Economic Letter, May 2014, "Middle-Skill Jobs Lost in U.S. Labor Market Polarization," by Anton Cheremukhin. ⓒ 2014 Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas. All rights reserved.

http://www.dallasfed.org/assets/documents/research/eclett/2014/el1405.pdf

2. American Economic Review, May 2013, "The Growth of Low-Skill Service Jobs and the Polarization of the U.S. Labor Market," by David Autor and David Dorn. ⓒ 2013 American Economic Association. All rights reserved.

http://economics.mit.edu/files/8152

|  |

The Middle-Class Jobs Crisis

Perhaps the biggest challenge facing the United States in the coming decade is the decline of its traditional middle class. This group, which made up about 60 to 80 percent of the population, was crucial to our global dominance throughout the Mass Production era.

Like few other countries, American culture was defined from the late 19th century by mass media markets, mass consumer markets, and relatively homogenous social values, all personified by the middle class.

For the most part, these people lived in nuclear families and owned homes, automobiles, telephones, and televisions. Most of them watched a few television networks; they mostly attended public schools; most were at least nominally Christian or Jewish; they mostly trusted business and the government; and they felt life would be even better for their children than it was for them.

This perception rested on an economic system that provided a typical high school graduate with an ample opportunity to find a job that paid enough to fund these needs, and even offered many life-long careers with a single employer. When coupled with a growing social safety net for retirees, this middle-class ideal became the "dream" to which immigrants and others around the world aspired.

________________________________________

Unfortunately, as the Mass Production Revolution matured and gave way to the Digital Revolution, this middle-class ideal began to fray. Now, over forty years from the dawn of the Digital Revolution, that fraying is still driven by a number of intersecting trends.

It manifests itself in The Battered American Dream trend we examined in the February 2015 issue of Trends. The chief outgrowth of that trend is the realization that Americans still seek opportunity, but they have become increasingly demoralized about the likelihood of achieving it.

To understand what lies ahead, its necessary to understand that 20th century America was unique in history and why the future will be different and, quite possibly, even better. Lets start by examining the confluence of factors that made American middle-class affluence in the 20th century the envy of the world.

First, the United States is uniquely blessed in terms of military security, agricultural productivity, and mineral wealth (including iron, coal, and oil) as well as logistical resources like harbors, rivers, and a lack of physical barriers. Because the U.S. seldom needed to worry about foreign invasions or shortages of natural resources, it was free to devote itself to economic development. It imported the technologies and entrepreneurial values that had enabled the first Industrial Revolution in England. In the egalitarian culture of the United States, these flourished and evolved through the Railroad Revolution, and the Steel Revolution set the stage for the Mass Production Era. European immigrants looking for a better life came to the United States and assimilated into it. Coupled with the enormous leap in agriculture productivity, immigration provided an unprecedented wave of semi-skilled labor ready to embrace the Mass Production Paradigm.

Second, the Mass Production Paradigm was ideally suited to the American society that existed at the beginning of the mass production era in 1908. Those Americans had some of the best literacy rates in the world, even though a minority had even a high school diploma. Raw materials were plentiful, railroads and canals provided cheap transportation, economies of scale were important, and the automation of agriculture freed up workers for the new factories. This led to a virtuous, self-reinforcing cycle: An increasing number of workers with medium skills produced ever greater quantities of ever cheaper goods, which were then sold to those workers through ever more efficient distribution channels to fulfill ever-expanding needs that were promoted through ever more influential mass media.

Third, the mass market depended upon several factors: economies of scale in production, standardized tastes, and strong worker productivity growth equaling or lagging the growth in demand. This harmony collapsed during the Great Depression, but came roaring back after World War II. In addition to the defense-driven capital investment, the depression and war years adapted societal institutions to optimally support the Mass Production model; those included consumer finance, effective banking regulations, and a middle-class social safety net, starting with Social Security retirement, then disability insurance, and finally Medicare. More significantly, the destruction of productive capacity in Europe and Asia during the war created an historic window of opportunity for U.S. businesses to create worldwide brand equity, production scale, and distribution channels. Americas middle-class workers rode this unprecedented wave of "economic imperialism," never suspecting that this brief era would not become their "new normal."

Fourth, middle-class values like thrift, marital fidelity, and honesty created a relatively homogenous society, in which everyone aspired to the middle-class practices and appearances presented on network television. And it was this standardized ideal that encouraged consumption of the kind of goods and services that could most readily be mass-produced.

________________________________________

However, that model began to reach its limits in the late 1960s and early ‘70s. The ‘70s saw the Mass Production Revolution plateau. Coincidently, we witnessed the birth of the Digital Revolution. But, even as the ‘80s and ‘90s saw the takeoff of the personal computer and the Internet, the institutions of the Mass Production Revolution stayed in place. Just as Americas middle-class workforce benefited from the extraordinary situation in the ‘50s, ‘60s and even ‘70s, it has suffered increasingly from the mismatch between our economic institutions and the demands of the Digital Revolution.

The clearest example is the ever-growing polarization in the workforce. The increase in the proportion of high-skill and low-skill jobs relative to the middle-skilled became evident about two decades ago. The U.S. labor market did not experience much polarization in the 1980s: Low-skill jobs were replaced by high-skill jobs, while the number of middle-skill jobs remained largely unchanged. Instead, polarization began about 25 years ago in the early 1990s, and intensified in the last decade.

In a recent report from the Dallas Fed, economist Anton Cheremukhin examined how the evolution of the economy drove this polarization.1 As Cheremukhin shows:

"Employment in the United States is becoming increasingly polarized, growing evermore concentrated in the highest-paying and lowest-paying occupations. Market changes involving middle-skill jobs in the U.S. are hastening labor market polarization. The distribution of jobs by skill level has shifted dramatically since 1980. The number of jobs requiring medium levels of skill has shrunk, while the number at both ends of the distribution - those requiring high and low skill levels - has expanded.

________________________________________

"This declining prominence of middle-skill jobs is not driven by changes in labor market institutions, such as declining unionization. Rather, an increase in automation of routine tasks, a relative scarcity of skilled workers and to a lesser extent, relocation of jobs outside the country have led to the relative expansion of two kinds of jobs in the U.S. The number of people performing low-skill, low-pay, manual labor tasks has grown along with the number undertaking high-skill, high-pay, nonroutine, principally problem-solving jobs.

"These changes have been relatively abrupt, with losses in routine employment concentrated in the recessions of 1990-91, 2001, and especially 2008-09. Unlike with earlier downturns, middle-skill jobs were not recovered in the expansions that followed these contractions."

________________________________________

To understand whats really happening, you have to look at the underlying nature of the jobs that people do. When the government collects data on jobs, occupations are classified into four categories:2

1. Cognitive nonroutine jobs are usually high-skill jobs that require performing abstract tasks, such as problem-solving, intuition, and persuasion. These typically require a college degree.

2. Manual nonroutine jobs are mostly low-skill jobs that involve manual tasks and require personal traits such as situational adaptability, visual/language recognition, and in-person interaction. These usually do not require a high school diploma.

3. Cognitive routine jobs are middle-skill jobs that require the ability to follow precise, well-understood procedures, which can be carried out by a computer. Often, middle-skill jobs require a high school diploma or even a higher level of education.

4. Manual routine jobs are lower-skill jobs that require the ability to follow well-understood procedures, which cant easily be carried out by a computer. These jobs often dont require a high school education.

Routine jobs declined from 58 percent of U.S. employment in 1981 to 44 percent in 2011, while both types of nonroutine jobs have expanded. Out of the overall routine job decline of 14 percent, 10 percent were replaced by higher-paying high-skill (nonroutine cognitive) jobs - the remaining 4 percent were downgraded to lower-paying low-skill (nonroutine manual) jobs.

The biggest declines in cognitive routine jobs were concentrated in such occupations as administrative support and sales. Examples of rapidly declining jobs are clerks, tellers, cashiers, telemarketers, title examiners, bookkeepers, insurance underwriters, travel agents, and technicians. Among the manual routine jobs on the decline are mail carriers, drivers, cooks, and engravers.

So what is behind this shift and how does it relate to the misfit between the characteristics of institutions optimized for the Mass Production Era and the characteristics needed for the Digital Era?

First, organized labor was a major institution defining the labor markets of the Mass Production Era. Its in heavily unionized sectors, such as manufacturing and government, where the United States has lost its competitive edge.

Today, foreign automakers supply the U.S. market from non-unionized plants in the United States. Grudgingly, American unions have eased work rules to enable the shrunken domestic manufacturers to compete. More commonly, unionized companies have turned increasingly to off-shoring for routine work.

Second, women were hit much harder than men by the disappearance of middle-skill jobs, especially the routine cognitive occupations. However, they have also been more willing to upgrade their skills and find better-paying jobs.

By comparison, more than half of men who lost middle-skill jobs, largely of the nonroutine manual type, had to settle for lower-paying occupations. Womens higher rates of education attainment in recent decades is a major reason for this difference.

Third, that raises perhaps the biggest disconnect between mass production institutions and those needed to support a workforce that can create and fill middle-skilled middle-class jobs. The mass production model required a vast pool of nonroutine manual workers and routine cognitive workers. But both categories of jobs are rapidly being automated away.

Today, cognitive nonroutine jobs require a college degree or even graduate school. Since too few people have been coming out of high school prepared to pursue vocationally valuable degrees, the rate of increase in the ratio of workers with a college degree relative to those with a high school diploma flattened in the early 1980s.

The result has been a steep rise in the "college earnings premium," which rose from just 10 percent in 1982 to 100 percent in 2008. One reason why so many men were unable to find higher-paying jobs and settled for lower-paying occupations is their relatively lower level of education.

Fourth, a final factor leading to the decline of the middle class has been that those middle-skilled workers whove lost their jobs have often had to enter routine manual occupations with stagnant or declining wages.

As the trend titled The Great Immigration Job Grab in our August 2014 issue clearly showed, immigrants have filled every net new job created since 2000.

In the case of the PhD from India or China, this fills an important shortfall in terms of nonroutine cognitive talent. However, the gardener from Mexico or the waiter from Nicaragua all too often serves to depress the wages of those formerly middle-class Americans.

Given this trend, we offer the following forecasts for your consideration:

First, organized labor will become largely irrelevant within the next ten years, eliminating barriers to education reform as well as optimum work rules.

While private-sector unions are already irrelevant in most sectors and geographies, public-sector unions still represent the largest impediment to education and regulatory reform. However, both public opinion and political momentum have recently shifted against them. Historic bastions of organized labor, such as Ohio, Indiana, Michigan, Wisconsin, and even Illinois are taking actions to weaken public-sector unions.

Second, the North American Energy Revolution, as well as the emerging "manufacturing renaissance," will create a significant number of manual nonroutine jobs over the next decade.

Despite the recent turmoil in the oil markets, the energy boom is here to stay. Between exploration, transportation, and refining, a whole host of new American jobs is being created. Similarly, manufacturing is returning to the United States as our costs are becoming highly competitive once more.

Third, the Deployment Phase of the Digital Techno-Economic Revolution will create a wave of new cognitive nonroutine jobs.

Breaking the grip of public-sector unions as previously discussed will enable us to redesign both K-12 and tertiary education with a clear focus on nonroutine manual and cognitive vocational skills.

Fourth, as soon as 2018, the United States will revamp its immigration policy to benefit the American worker.

Todays immigration policy is not well suited to meeting the needs of employees or employers. A future policy will proactively recruit the best minds from around the world to come to the U.S. as researchers and entrepreneurs. At the same time, it will rigorously close our borders, identify those living here illegally, and only permit companies to hire those needed by the economy. Thirty years ago, this would have been prohibitively expensive; but with todays technology, its merely a political decision.

References

1. Economic Letter, May 2014, "Middle-Skill Jobs Lost in U.S. Labor Market Polarization," by Anton Cheremukhin. ⓒ 2014 Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas. All rights reserved.

http://www.dallasfed.org/assets/documents/research/eclett/2014/el1405.pdf

2. American Economic Review, May 2013, "The Growth of Low-Skill Service Jobs and the Polarization of the U.S. Labor Market," by David Autor and David Dorn. ⓒ 2013 American Economic Association. All rights reserved.