|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

| 미디어 브리핑스 | 내서재담기 |

|

|  |

스탠더드 오일Standard Oil, AT&T, IBM은 모두 연방 정부의 독점금지법에 따라 규모 축소를 경험한 기업들이다. 오늘날, 구글과 아마존, 페이스북, 애플도 독점 시비에 휘말려 있다. 그렇다면 이들도 과거의 기업들과 유사한 운명을 맞게 될까? 인터넷 시대의 독점금지법에 관한 이해가 필요하다. 규제와 이슈는 무엇일까?

지난 120년 동안, 독점금지법은 스탠더드 오일Standard Oil, IBM, AT&T 등과 같은 독점 기업들이 시장을 장악하는 것을 막아왔다. 그리고 이제 이 법은 인터넷 시대에 맞춰진 유사한 공격을 다시 전개할 태세다. 무슨 일이 일어나고 있는가?

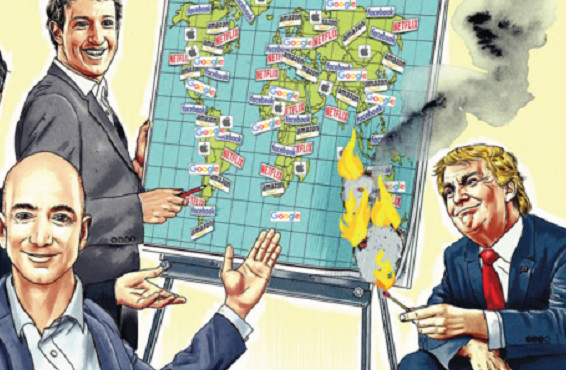

페이스북Facebook, 아마존AMAZON, 애플Apple, 구글Google 및 넷플릭스Netflix 등의 IT 거인들이 그 주인공으로 이들은 공격적인 독점금지법의 집행과 곧 직면할 것 같다. 사실, 오바마 대통령의 국정 수행 기간 동안, 실리콘 밸리의 가장 큰 기업들은 조심스럽게 백악관 사람들의 환심을 사기 위해 노력했었다. 그러나 현재, 이들 인터넷 독점 기업들의 워싱턴 친구들의 수는 극적으로 줄어들었고, 의회에서 가장 친했던 친구들도 소수 세력으로 전락했다. 친근했던 규제기관이 이제 그들에게 의심의 혜택the benefit of the doubt(증거불충분으로 인한 무죄 추정)을 제공할 이유가 거의 없는 세력으로 빠르게 대체되고 있다.

사법부 또한 이들에게 점점 멀어지려는 태도를 보여주고 있다. 미국 이외 지역의 규제 환경도 그다지 우호적이지 않다. 2017년 6월 27일, EU는 독점 혹은 불공정 무역관행 혐의로 구글에 27억 달러(한화 약 3조 207억 원)의 벌금을 부과했다. 구글은 항소했고, 현재 방어를 준비 중이다. EU의 주장은 구글이 검색 엔진과 스마트폰 운영체제의 지배력을 부당하게 남용하여 쇼핑 서비스, 광고 위치 서비스, 스마트폰 앱 스토어 마켓에서 경쟁을 방해했다는 것이다.

오늘날의 독점 대상은 규제 당국이 과거에 활용했던 전통적인 통계 방식의 압박 대상과는 다르다. 이것은 규제 당국이 도전해야 하는 새로운 주제임이 확실한데, 바로 21세기의 새로운 ‘정보 독점’을 다루기 때문이다. 보스턴컨설팅그룹Boston Consulting Group 전문가들에 따르면, “다가오는 반독점 전투는 전통적 의미에서 시장을 통제하는 것이 아닌, 소비자 정보에 관한 통제를 다루는 전투일 것이다.”

오늘날 IT 거대 기업들은 더 개선된 형태의 디지털 소비자 모형 구축 경쟁을 벌이고 있다. 이것은 사용자 데이터를 수집하는 것뿐만 아니라 경쟁 업체가 동일한 일을 하기 더 어렵게 만드는 방법을 찾는 것이다. 따라서 미래의 독점은 이들이 소비자들에게 얼마나 팔 것인지로 측정할 수 없다. 즉, 이들이 경쟁자보다 소비자에 대해 얼마나 많이 알고 있고, 행동을 얼마나 더 잘 예측할 수 있는지에 따라 독점 판단이 결정될 것이다.

따라서 새로운 전투는 모든 개인들의 디지털 모형 구축에 대한 통제에 있다. 구글, 페이스북, 아마존, 애플 및 기타 ‘디지털 거인들’은 이미 이 영역에서 독점을 얻기 위한 싸움에 임하고 있고, 모든 사람들의 더 완벽한 디지털 모형을 보유하기 위해 치열한 경쟁을 치르고 있다. 이러한 전투가 심화됨에 따라 거인들 스스로도 상대적 우위를 정확하게 측정하는 데 필요한 기준을 갖추지 못할 수도 있다. 더군다나 독점금지법 집행자들은 잠재적인 독점 효과를 막을 수 있는 준비조차 아직 갖추지 못하고 있다. 이것이 바로 오늘날 디지털 세계의 독점에 있어 본질적인 문제다.

구글이 자사의 검색 엔진을 개발했을 때, 그들은 개인들의 디지털 모형 구축을 향한 여정이 시작될 것으로 생각하진 못했을 것이다.

그러나 소비자가 수행하는 모든 검색은 그 소비자의 특정한 면을 구글에게 제공해준다. 마찬가지로 우리가 넷플릭스를 통해 시청하는 모든 영화, 우리가 아마존의 인공지능 알렉사Alexa 혹은 애플의 시리Siri에게 묻는 모든 질문, 페이스북에서 친구들과 함께한 모든 상호작용은 우리 개인들의 다양한 면모를 이들에게 보내고, 이들 디지털 거인들이 구축하는 완벽한 디지털 모형 구축에 기여를 하게 된다.

이들이 개개인들의 다양한 면면들을 포착하기 위해 사용하는 사람들이 생각할 수 있는 모든 것들을 시도하고 있다는 것은 놀라운 일이 아니다. 부분적으로 이것은 일반적인 기술 서비스의 외곽, 즉 자동차나 헬스케어와 같은 영역에서 이들이 다양한 노력을 시도하는 이유가 될 수 있다. 자동차는 우리 행동에 관한 값진 정보를 제공해줄 수 있다. 아마존과 같은 디지털 거인은 알렉사를 통해 우리가 집안의 모든 가전제품을 포함해 기타 물건들과 어떻게 상호 작용하는 지에 관심을 두고 있다.

역사적으로 기업들은 개인 삶의 특정 측면에 대한 깊은 지식을 가지고 있었다. 예를 들어, 금융 기관은 고객의 재정적 삶을 잘 파악하고 있었다. 소매업체들은 그들 고객의 구매 습관에 관한 지식을 축적했었다. 심지어 도서관도 이용자의 독서 습관에 대한 정보를 갖고 있었다. 그러나 그들에게 부족했던 것은 그러한 정보들을 모두 모아야 가능한 ‘개인에 관한 종합 지식’이었다. 경쟁이 분야별로 이뤄졌기 때문에, 기업들은 그러한 정보를 취합할 동기를 갖지 못했다. 더욱이 이질적인 (혹은 자신에게는 필요 없는) 정보를 모으는 일은 번거로운 작업이었다. 따라서 기업들은 그러한 노력과 시도를 위해 재원을 쓸 이유를 찾지 못했다. 즉, 디지털 모형의 아날로그 버전은 다양한 시장 참여자들에 의해 보유되었던 개인의 부분 사진일 뿐이었다.

그러나 이제 디지털 시대의 도래로 인해 그 사진이 완전히 변하고 있다. 구글, 아마존, 페이스북과 같은 디지털 거인들은 이제 완벽한 디지털 모형을 갖추는 것이 (그들에게) 바람직할 뿐만 아니라 실현 가능하다는 것을 인식하고 있다. 그들에게 이것이 바람직한 이유는 여기에는 엄청난 교차 판매 및 광고 기회가 있기 때문이다. 그리고 경쟁자보다 앞서 선점하는 기업에게 더 유리하다는 것도 알고 있다.

디지털화가 우리 삶을 감싸고 있는 방법, 디지털 세상에서 상호 작용할 때 디지털 흔적을 일상적으로 남기는 방법으로 인해 이것은 현실화가 되고 있다. API와 같은 기술을 통해 이들 기업들이 그들이 보유한 정보의 각기 다른 조각들 혹은 면모들을 공유하거나 접근하는 것을 더 수월하게 만들고 있다.

고객 선호도와 연계된 고품질 데이터에 관한 접근성을 기업이 추구하고 있다면, 다양한 소스로부터 얻은 데이터를 수집, 연결, 통합하는 역량이 새로운 경쟁 장벽이 될 것이다. 이 장벽은 다른 경쟁자가 개인별 디지털 모형에 접근하고 통제하려는 것을 막아줄 것이다.

이러한 새로운 형태의 독점은 전통 산업에 집중된 수단과 방법으로는 보이지 않으면서 소비자에 대한 가공할만한 영향력을 행사한다.

이러한 독점의 매력은 독점 기업들이 그들이 보유한 정보를 기반으로 전례 없는 개인 맞춤화를 제공할 수 있는 능력일 것이다. 그러나 이러한 개인 맞춤화에 따라 고객은 정보 제공자들이 원하는 것만 볼 수 있도록 제한 받게 될 것이다.

전통 시장에서는 독점 기업을 색출하기가 수월했다. 그러나 개인이 생각하고 행동하고 일상적인 결정을 내리는 방식에 접근하는 독점은 발견하기 쉽지 않다. 개별 맞춤화된 서비스의 편리성 때문에 디지털 모형에 대한 독점적 접근을 제공하고 있는 개인들은 자신들의 선택이 자신이 아닌 공급자에 의해 유도된 것임을 결코 깨닫지 못할 수도 있다.

요컨대 디지털 모형을 구축하기 위한 데이터 수집은 수많은 형태로 나타날 수 있다. 이러한 데이터 탐색과 수집은 제대로 작동하는 시장 시스템 유지에 촉각을 세우는 규제 당국에게 큰 숙제를 안겨주었다. 디지털 거인들이 다양한 영역에 걸쳐 촉수를 뻗치고 데이터의 소유권을 확대함에 따라, 이들은 경제학자들이 이상적으로 생각하는 원자적 경쟁atomistic competition이 불가능할 수 있는 세상을 만들고 있는지도 모른다. 원자적 경쟁이란 동일한 경제주체들이 상호교류없이 시장의 시그널(가격 신호)만 보고 의사결정을 내리는 완전경쟁 모형으로, 어떠한 주체도 지배적이지 못한 구조를 의미한다.

이 새로운 환경의 보다 복잡한 역학 관계에 상관없이, 구글이 그들의 독점력을 반경쟁적anti-competitive으로 사용한 점은 사실이고 소송을 초래할 수 있음은 분명하다. 결과적으로, EU는 적어도 세 가지 논리에 근거하여 구글의 독점력 남용에 대한 심각한 반독점 조사를 계속 진행하고 있다.

첫 번째는 구글이 인터넷 검색 시장에서 독점적 지위를 사용하여 검색 결과에서 자체 제품을 체계적으로 우선시했다는 것이다. 사람들은 구글의 검색 서비스가 자신의 검색 질의에 가장 관련이 있는 객관적 알고리즘을 사용하고 있다고 가정한다. 그러나 실제로 일어난 일은 구글이 경쟁사의 제품이나 서비스에서 일어나야 할 트래픽을 구글의 것으로 인위적으로 전환하기 위해 화면에서 가장 눈에 띄는 위치에 자사 제품이나 서비스를 게재한다는 것이다.

두 번째는 구글이 모바일 운영 시스템(전 세계적 독점인 안드로이드 시스템)에서의 독점적 지위를 사용하여, 일반 인터넷 검색과 소비자 데이터 수집에 대한 독점을 3가지 방식으로 유지하고 강화했다는 것이다.

1. 모바일 기기 제조업체들이 구글 서치Google Search 및 구글 크롬Chrome브라우저를 기기내 사전 설치하도록, 구글의 독점적 앱 라이선스 취득을 조건으로 기기의 기본 검색 서비스를 구글 서치로 설정하도록 강요함.

2. 아마존의 킨들 파이어Kindle Fire와 같은 안드로이드의 ‘오픈 소스’ 코드에 기반한 경쟁 운영 시스템을 사용하는 모바일 기기를 제조업체들이 판매하지 못하게 함.

3. 제조업체와 모바일 네트워크 사업자들이 그들 기기에 구글 서치를 사전 설치하는 조건으로 (유료 우선권paid prioritization의 형태로) 금전적 인센티브를 제공.

구글은 자체 검색 제품에 대한 메뉴를 통제하는 것과 똑같은 방식으로, 전 세계 모바일 기기에 대한 메뉴 제어를 위해 이러한 전략들을 사용하고 있다.

세 번째는 구글이 사용하는 전략으로 인터넷 광고에 있어 구글의 독점적 지위 그 자체다. 구글은 이 독점적 지위를 활용하여 자체 검색 및 광고 서비스를 선호하게 강요한다. 검색 광고를 통한 구글 수익의 상당 부분은 구글과 독점 계약을 맺은 수많은 제3자로부터 발생한다. 약 10년 동안 이러한 계약은 제3자들에게 다음과 같은 것들을 요구해왔다.

- 구글 경쟁업체들의 검색 광고 소스 사용을 거부할 것

- 구글을 통한 최소 수의 기본 광고를 받아들이고, 구글 검색 광고를 위해 프리미엄 공간을 준비해둘 것

- 경쟁 검색 광고 게재를 변경하기 전에 구글의 승인을 얻을 것

미 연방통상위원회Federal Trade Commission의 내부 보고서에서 구글이 독점력을 강화해오고, ‘소비자 복지에 지속적으로 부정적 영향을 미칠’, 그리고 ‘소비자와 혁신에 실질적인 해악’을 초래한 차별 행위에 의도적으로 관여했음을 발견했다. 그러나 이러한 발견에도 불구하고, 미국은 소소한 조치만 취한 후 구글에 대한 조사를 종결했다.

이렇게 종결된 연방통상위원회의 조사를 분석한 후, 〈월스트리트 저널The Wall Street Journal〉은 구글에 관한 반독점 소송이 그들과 가장 친근한 기업 동맹들 중 하나인 오바마 행정부의 오점이었을 것이라고 언급했다. 구글은 오바마의 재선 시도에 있어 캠페인 기부금 제공 기업 중 두 번째로 큰 기업이었다. 이 어색한 상황은 오바마 행정부가 왜 구글에게 ‘통행권’을 제공했는지를 잘 설명해준다.

이외에도 오바마 재직 기간, 구글이 오바마 대통령과 민주당에게 검색 특혜를 제공했다는 증거도 있다. 즉, 연방통상위원회의 조사 결과가 상업적 측면에 집중했지만, 구글이 여러 가지 이유로 다른 검색 결과를 조작한다는 증거도 존재한다. 즉, 보수적 의견보다는 진보적 의견을 더 지원하는 검색 결과를 내놨다는 것이다. 더욱이 그 기간, 공화당과 민주당의 정치인들은 모두 구글의 독점 남용이 초래한 공정한 경쟁과 소비자에 대한 유해성을 무시하는 데 있어 책임이 있다.

그렇다면 구글이 실제로 투표자 행동에 영향을 끼칠 수 있을까?

불행하게도 각종 연구는 구글이 검색 결과를 활용할 수 있음을 보여 주고 있다. 이론적으로도 이것은 가능한 일이다. 미 국립과학원 회보PNAS, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 연구 논문집에 발표된 5개의 이중 맹검二重盲檢, double-blind 무작위 통제 실험 결과에 따르면 ‘편향된 검색 순위가 누구를 지지할 것인지 결정하지 못한 유권자들의 투표 선호도에 20% 혹은 그 이상으로 영향을 미칠 수 있음’이 밝혀졌다. 이 연구 결과는 모두 구글과 같은 지배적 검색 엔진이 ‘어떤 처벌도 받지 않고 투표 결과에 영향을 주는 힘을 갖고 있다’는 점을 보여준 것이다.

더군다나 미디어에 영향을 미치는 구글의 힘은 검색 엔진을 훨씬 능가한다. 구글의 더블클릭Double Click 서비스는 광고 서버 시장을 지배하고 있다. 더블클릭은 광고 서버를 활용하는 모든 웹사이트의 75%에 광고를 공급한다. 구글은 미국 미디어 그룹 가넷Gannett과 뉴욕 타임스New York Times와 같은 기업들과 제휴를 통해 미 전역의 대다수 디지털 신문과 지역 텔레비전 방송 웹사이트에 광고를 제공한다.

신문들은 광고 수입에 크게 의존하는 구조이기 때문에, 디지털 광고에 대한 구글의 통제는 구글이 저널리즘의 주요 수입 흐름을 통제하고 있다는 의미가 된다. 〈USA 투데이USA Today〉와 전 세계 지역에서 수많은 신문을 발간하는 가네트는 2016년 연례 보고서에서 지역 광고 서비스가 ‘지역 온라인 광고 산업에 영향을 미치는 구글의 비즈니스 관행과 관련된 새로운 개발이나 소문’에 의해 악영향을 받을 수 있다고 언급했다.

이것은 새롭게 떠오른 우려 사항이 아니다. 1999년을 되돌아보면, 더블클릭 창립자는 언론, 각종 매체 등 수많은 발간물들을 하나의 광고 네트워크로 묶는 것의 위험성을 인식했다. 즉, 그 네트워크가 그들을 움직이게 하는 미디어와 광고 에이전시보다 더 강력한 힘을 가질 수 있다는 것이다. 그러한 우려는 구글이 2008년 더블클릭을, 2010년에 애드몹AdMob을 인수하면서 현실화가 되었다.

이러한 심각함에도 불구하고 다행스러운 점은 구글의 엄청난 독점력이 아직까지는 제한적이라는 데 있고, 독점금지법이 이러한 문제를 해결할 수 있다는 점이다. 예를 들어, 독점금지법은 구글의 해체 혹은 축소, 더블클릭과 에드몹 인수 취소를 단행할 수도 있다.

이러한 독점금지와 관련된 21세기의 새로운 과제는 앞으로 다음과 같이 예측할 수 있다.

첫째, 앞으로 미 연방통상위원회와 법무부는 주요 독점금지 조사 대상을 발표할 가능성이 크다.

페이스북, 아마존, 애플, 구글이 가장 가능성 있는 대상이다. 그리고 2022년까지 비디오 및 음원 스트리밍을 비롯하여 온라인 광고와 전자 상거래 등에 대한 독점금지 조치가 시행될 것이고, 사회적 공감대 또한 새롭게 형성될 것이다.

둘째, 구글이나 페이스북과 같은 플랫폼이 공공 유틸리티처럼 규제될 가능성이 높을 것이다.

규제 이유는 인구의 대다수가 사용하는 검색 엔진이나 소셜 네트워크는 공정하고 올바르게 균형 잡혀야 하기 때문이다. 특정 정당의 이익을 대변하거나, 그러한 엔진과 네트워크를 운영하는 기업들의 이해가 우선시 되는 관행에 제동이 걸릴 것이다. 물론 이것은 법적으로 결정될 사안이다.

셋째, 독점금지가 진행되면서, 기존 강자들이 혼란에 빠지고 새로운 승자들이 등장할 것이다.

지난 역사를 보면 석유에서 컴퓨팅, 통신 분야에 이르는 영역에서, 독점금지는 급진적 혁신과 새로운 폭발적 성장을 항상 예고해왔다. 21세기의 새로운 독점금지에 대한 과정에서도 새로운 혁신 기업들이 살아남아 새로운 영역과 공간을 창출할 것이다. 조사 결과가 발표되면 아마존, 구글, 페이스북 등의 주가는 타격을 입을 수도 있다. 하지만 산업 전체 분야의 가치는 더 커지는데, 이것은 새로운 혁신 기업이 뛰어들기 때문이다.

* *

References List :

1. The New York Times. JUNE 27, 2017. Google Fined Record $2.7 Billion in E.U. Antitrust Ruling by MARK SCOTT.

https://www.nytimes.com/2017/06/27/technology/eu-google-fine.html?_r=0

2. Wall Street Journal. March 19, 2015. Inside the U.S. Antitrust Probe of Google by Brody Mullins, Rolfe Winkler and Brent Kendall.

https://www.wsj.com/articles/inside-the-u-s-antitrust-probe-of-google-1426793274

3. The search engine manipulation effect (SEME) and its possible impact on the outcomes of elections by Robert Epstein and Ronald E. Robertson. (Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2015, vol. 112 no. 33, E4512?E4521, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1419828112.)

http://www.pnas.org/content/112/33/E4512.full

4. Wall Street Journal. Nov. 21, 2016. Google Search Results Can Lean Liberal, Study Finds by Jack Nicas.

https://www.wsj.com/articles/google-search-results-can-lean-liberal-study-finds-1479760691

5. Hollywood Reporter, Feb. 21, 2017. Michael Wolff on Trumps Tech War and How Big Media Benefits by Michael Wolff.

http://www.hollywoodreporter.com/news/michael-wolff-trumps-tech-war-how-big-media-benefits-977254

|  |

Trust-Busting in the Internet Age

Over the past 120 years, trust-busting regulators have disrupted vast monopolies enjoyed by the likes of Standard Oil, IBM, and AT&T. And now, they appear poised to roll-out a comparable offensive designed for the Internet age.

FACEBOOK, AMAZON, Apple, Google, and Netflix are likely to face aggressive trust-busting enforcement, especially if Donald Trump serves two terms.

During the Obama years the largest Silicon Valley firms carefully courted the people in the White House, even as their down-ballot allies were decimated. Today, the “Internet Robber Barons” have dramatically fewer powerful friends left in Washington or most of the state capitals. Their best friends in Congress are in the minority. Friendly regulators are being rapidly replaced by those who have little reason to give them the “benefit of the doubt.” And, with many vacancies to be filled, the judiciary is taking on a less friendly demeanor as each day passes.

Outside the United States, the regulatory environment has been less-than-friendly for some time. On June 27, 2017 the EU fined Google $2.7 billion for alleged monopolistic or unfair trade practices. Google has appealed and is now preparing its defense.

The EU’s case asserts, among other things, that Google unfairly exploits its dominance in search engines and smartphone operating systems to restrict competition in shopping services, ad placement services, and smartphone app store markets.

Furthermore, today’s monopolies are not just pushing hard against the traditional metrics used by trust-busters, but they are building new 21st century “info monopolies” that regulators are almost certain to challenge. According to experts at the Boston Consulting Group, “the coming battle in antitrust will not be about controlling markets in the traditional sense. It will be about the battle for control over consumer information. The tech titans are currently in a race to see which of them can build a better digital replica of their consumers, which means finding a way not just to collect user data but also to make it harder for competitors to do so. Tomorrow’s monopolies won’t be able to be measured just by how much they sell us. They’ll be based on how much they know about us and how much better they can predict our behavior than competitors.”

The new battle is for control of the digital replica of every individual. Google, Facebook, Amazon, Apple and other such “digital titans” are already battling for dominance in this realm, fighting over who possesses a more complete digital replica of the most individuals. As this battle intensifies, even the titans themselves may not have the necessary metrics to accurately gauge their relative dominance. And antitrust enforcers are a long way from being equipped to guard against its potential anti-competitive effects. Yet this is where the digital world is taking us.

When Google developed its search engine, it probably never thought that it would start a journey toward building digital replicas for individuals. Yet, every search a consumer conducts offers select facets of his persona to Google. Similarly, every movie we watch through Netflix, every question we ask Alexa or Siri, and every interaction we have with our friends on Facebook imparts different slices of our persona, each contributing to a full digital replica of ourselves built by a digital titan. It is not surprising that these titans are trying everything they can think of to capture different facets of our personas. This in part explains many of their recent forays outside of traditional tech services into domains such as automobiles and health care. A car can provide a treasure trove of information about our behavior. A digital titan such as Amazon is interested in how we interact with a whole host of appliances and other objects in our homes through Alexa.

Historically, many firms have had deep knowledge about only specific facets of an individual’s life. For example, financial institutions knew the financial lives of their customers; retailers accumulated knowledge about their customers’ buying habits; and even libraries had information on users’ reading habits. What they lacked, however, was a composite knowledge about individuals that came through the pooling of such information. Since competition was sector-by-sector, firms did not have the incentive to pool such information. Moreover, pooling disparate information was an onerous task, and no firm had the desire to expend resources on such an effort. In other words, the analog versions of digital replicas were only partial pictures of individuals possessed by different market participants.

But now, the arrival of the digital age has changed this picture completely.

Digital titans like Google, Amazon, and Facebook now recognize that having a complete digital replica is not only desirable but also feasible. It is desirable because of enormous cross-selling and cross-advertising opportunities that will accrue for the firm that gets there ahead of others. And it is becoming feasible because of how digitization has enveloped our lives, how we routinely leave digital traces as we interact in the digital world, and through technologies, such as APIs, that are making it easier for companies to share or access different slices of information that they possess.

If access to high-quality data on customer preferences is what companies are seeking, the ability to collect, connect, and integrate data from various sources will become the new competitive barrier. This barrier will restrict other competitors from gaining access to and control over individual digital replicas. Such new-age monopolies may not be visible through traditional industry concentration measures, but they will wield tremendous influence over consumers. Their allure will be their ability to provide unprecedented personalization based on the information they hold. Yet with such personalization customers may be restricted to see only what the provider wants them to see.

Monopolies in traditional markets are easy to detect. But a monopoly in who gets access to how individuals think, behave, and make day-to-day decisions is not. Individuals getting lured into providing monopoly access to their digital replicas because of the convenience of personalized services may never realize that their choices are being made not by them but by their providers.

In sum, data acquisition for digital replicas can manifest itself in many forms. These quests for data may pose major challenges for regulatory authorities keen on maintaining a well-functioning market system. As digital titans expand their reach and ownership of data across multiple domains, they may create a world where the atomistic competition so beloved by economists may become impossible.

Regardless of the more complex dynamics of this new environment, it’s already clear that Google’s anti-competitive use of its monopoly power is real and actionable. As a result, the European Union is still conducting serious antitrust investigations into Google’s abuse of its monopoly power based on at least three lines of reasoning.

For one, Google uses its monopoly position in internet search markets to systematically favor its own products in its search results. People assume that Google’s search service uses an objective algorithm that gives them the most relevant responses to their search inquiries. What really happens is that Google shows its own products in the most prominent positions on the screen in order to artificially divert traffic from rival services to Google’s own. As former Google designer Tristan Harris describes it, “if you control the menu, you control the choices.”

Second, Google uses its monopoly position in mobile operating systems (Android is dominant worldwide) to preserve and strengthen its dominance in general internet search and over consumer data collection in three ways:

1. Forcing manufacturers to pre-install Google Search and Google’s Chrome browser and set Google Search as the default search service on their devices as a condition to licensing Google’s proprietary apps;

2. Blocking manufacturers from selling mobile devices that use competing operating systems that are based on Android’s supposedly “open source” code (like Amazon’s Kindle Fire); and

3. Giving financial incentives to manufacturers and mobile network operators on condition that they exclusively pre-install Google Search on their devices (a form of paid prioritization).

Google uses these tactics to ‘control the menu’ on the vast majority of the world’s mobile devices like Google controls the menu on its search products themselves.

And, the third, tactic Google uses is its dominant position in internet advertising to favor its own search and advertising services. A substantial portion of Google’s revenue from search advertising comes from a limited number of third-parties with whom Google has exclusive deals. For a decade, these deals required third-parties to:

- Refuse to source search ads from Google’s competitors,

- Take a minimum number of ads from Google and reserve premium space for Google search ads, and

- Obtain approval from Google before making any changes to the display of competing search ads.

In the US, a Federal Trade Commission staff report found that Google intentionally engaged in discriminatory conduct that has strengthened its monopoly power and caused “real harm to consumers and to innovation” that “will have lasting negative effects on consumer welfare.” But, in spite of that finding, the U.S. closed its investigation of Google after giving it little more than a slap on the wrist.

In its investigative report of the closed FTC investigation, the Wall Street Journal noted that an antitrust lawsuit against Google would have pitted the Obama administration against one of its closest corporate allies, who “was the second-largest corporate source of campaign donations to President Barack Obama’s re-election effort.” This awkward situation could explain why the Obama administration gave Google a corporate pass, but that’s not the only possibility.

Google’s practice of censoring ideas and suppressing viewpoints that differ from their viewpoint, offers an equally powerful rationale for the Google “boosterism” by both the Obama administration, and the Democratic Party generally, during the Obama years. Though the Federal Trade Commission’s findings focused on commercial speech, overwhelming evidence exists that Google manipulates its search results for ideological reasons as well; that is, to suppress “nonpolitically correct” thought and support progressive causes. This is likely only the tip of the iceberg.

Eric Schmidt, Google’s Chairman, openly admits that search engines can “detect malicious, misleading and incorrect information [as defined by Google] and essentially have you not see it.… just take it off the page… Put it somewhere else. Make it harder to find.” For the Obama administration, prosecuting Google would have been akin to biting the hand that feeds them.

Moreover, during the Obama years, politicians on both sides of the aisle were complicit in ignoring the competitive and consumer harms that Google’s monopoly abuses caused, let alone the threat Google posed to American ideals and political candidates it does not favor.

In fact, researchers have shown that Google can use its search results to influence voter behavior and, at least in theory, determine the outcome of political elections. The results of five double-blind, randomized controlled experiments published in a Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences research paper, demonstrated that “biased search rankings can shift the voting preferences of undecided voters by 20 percent or more” with voters showing “no awareness of the manipulation.” The paper’s results suggest that a dominant search engine, like Google’s, “has the power to influence the results of a substantial number of elections with impunity.”

Furthermore, Google’s power to influence the media goes well beyond its search engine. Google’s DoubleClick service dominates the ad server market. DoubleClick serves ads to 75 percent of all websites that use ad servers. Google serves ads to the vast majority of digital newspaper and local television websites through relationships with entities like the Local Media Consortium, Gannett, and the New York Times. Because newspapers rely heavily on advertising revenue, Google’s control over digital advertising gives Google control over journalism’s primary revenue stream. As Gannet, the publisher of USA Today and scores of other newspapers around the globe, noted in its 2016 Annual Report, its local advertising service could be adversely affected by “any new developments or rumors of developments regarding Google’s business practices that affect the local online advertising industry.”

This is not a new concern. Way back in 1999, the founders of DoubleClick recognized the danger of assembling numerous publications into a single advertising network ? that it could become more powerful than the media and ad agencies for whom it works. They dismissed the problem by asserting that they would never compete with their clients in content. “That’s just a line” that shouldn’t have been crossed, they said. But thanks to lax antitrust enforcement, Google crossed that line when it to acquired DoubleClick in 2008 and AdMob in 2010.

Fortunately, despite its enormity, Google’s power to stamp out ideas and competitors is limited. And the antitrust laws offer a remedy. For example, the courts might undo Google’s acquisitions of DoubleClick and AdMob by breaking up Google. Only time will tell.

Given this trend, we offer the following forecasts for your consideration,

First, by the fall of 2018, major antitrust investigations will be announced by the FTC and the Justice Department.

FACEBOOK, AMAZON, Apple, and Google are the most likely targets. The most likely outcome is a set of consent decrees by 2022 opening on-line advertising and e-commerce, as well as streaming video & music to greater competition.

Second, it’s quite possible that platforms like Google and Facebook will be regulated like public utilities.

The rationale is that a search engine or a social network should be “fair and balanced,” giving the end-user the results that best fit his or her criteria, without subjective “value judgments.” This is very likely the kind of issue that can only be decided by the Supreme Court. And.

Fourth, as this trust-busting takes shape, existing powerhouses will be disrupted and new winners will be created.

In sectors ranging from oil to computing to telecom, trust-busting presaged a period of radical innovation and explosive growth. The same thing will happen as new innovators are able to commercialize cyber-space, without being strangled by today’s mega-players. When the investigations are announced, the stocks of Amazon, Google, Facebook and others will take a hit. However, value across the entire sector will end up increasing as new, even more innovative players, enter the arena.

References

1. The New York Times. JUNE 27, 2017. Google Fined Record $2.7 Billion in E.U. Antitrust Ruling by MARK SCOTT.

https://www.nytimes.com/2017/06/27/technology/eu-google-fine.html?_r=0

2. Wall Street Journal. March 19, 2015. Inside the U.S. Antitrust Probe of Google by Brody Mullins, Rolfe Winkler and Brent Kendall.

https://www.wsj.com/articles/inside-the-u-s-antitrust-probe-of-google-1426793274

3. The search engine manipulation effect (SEME) and its possible impact on the outcomes of elections by Robert Epstein and Ronald E. Robertson. (Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2015, vol. 112 no. 33, E4512?E4521, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1419828112.)

http://www.pnas.org/content/112/33/E4512.full

4. Wall Street Journal. Nov. 21, 2016. Google Search Results Can Lean Liberal, Study Finds by Jack Nicas.

https://www.wsj.com/articles/google-search-results-can-lean-liberal-study-finds-1479760691

5. Hollywood Reporter, Feb. 21, 2017. Michael Wolff on Trumps Tech War and How Big Media Benefits by Michael Wolff.

http://www.hollywoodreporter.com/news/michael-wolff-trumps-tech-war-how-big-media-benefits-977254