|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

| 미디어 브리핑스 | 내서재담기 |

|

|  |

중국은 미국이 지배하는 세계 구조로부터의 탈출을 꿈꾸고, 21세기를 지배하는 초강대국으로 나아가기 위한 행보를 이어가고 있지만, 현실은 어떠할까? 중국에서 현재 일어나고 있는 일을 관찰하면 이 질문에 대한 답을 어느 정도 구할 수 있다. 각종 난제에 직면한 중국, 나머지 세계에 끼치는 영향은 무엇인가? 이 과정에서 가장 큰 영향을 끼치고 있는 미국의 선택은 무엇일까?

.png)

워싱턴과 전 세계의 다른 국가들은 비교적 최근까지 이러한 전망에 익숙했다.

“우리 시대의 지정학적 이야기 중 하나는 중국의 부상으로 미국 중심의 헤게모니는 천천히 죽어갈 것이란 점이다. 베이징의 상승을 보여주는 징후는 세계 어느 곳에나 있다. 중국의 해외 투자는 전 세계에 퍼져 있고, 중국 해군은 주요 해로를 순찰하며, 남중국해는 천천히 식민지화되고 있다. 중국 정부는 내부의 반대자들을 단속하고, 전 세계에 거대한 (중화) 민족주의의 프로파간다를 추진하고 있다.”

그러나 최근 중국 내부의 여러 가지 문제와 국제 정서, 그리고 미국의 입장을 종합하면 이러한 전망은 잠시 보류해야 할 것 같다.

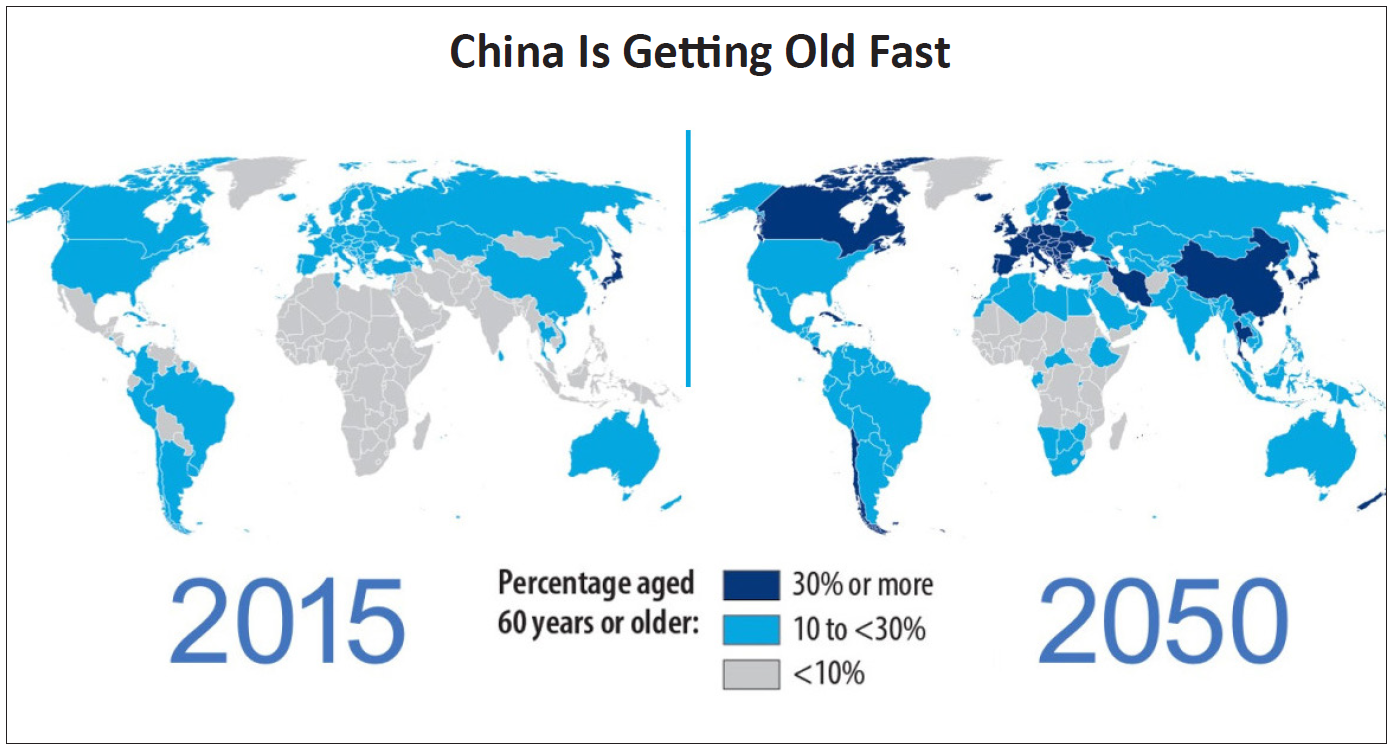

국제 사회에서 한층 더 높아진 중국의 목소리는 일면으로는 성장하고 있는 국력과 그들의 야망에 대한 표상으로 보인다. 하지만 사실을 좀 더 면밀히 보면 꼭 그런 것도 아니다. 오히려 지난 수십 년 간 세계를 놀라게 한 경제 성장과 국력 신장이 정체기를 맞고, 처음으로 경험하고 있는 지속적인 경제 둔화, 그리고 내부 불만에 대한 중국 지도자들의 불안이 반영된 것일 수도 있다. 실제로 2008년 금융 위기 이후 중국의 경제 상황은 꾸준히 악화되었다. 부채, 자원 고갈, 급속한 인구 고령화, 그리고 각 국가에서 발생하고 있는 보호주의의 강화로 인해 중국의 성장률은 절반으로 떨어졌고 앞으로 수년 내에 더 급락할 가능성을 보이고 있다.

중국의 경제 위기가 지속되면 장기적으로 그들의 경쟁력은 더 약화될 것이다. 그러나 이러한 위기는 미국에게 오늘날 더 큰 위협이 되고 있다, 왜 그럴까? 터프츠 대학교의 마이클 벡클리(Michael Beckley) 교수는 외교전문지 「포린 어페어스 Foreign Affairs」에서 “과거를 보면 떠오르는 강대국들은 둔화를 겪기도 한다. 그리고 그 상황이 되면 대분은 내부에서 더 억압적이고, 외부로는 공격적이 되었다. 중국도 그러한 길을 걷고 있는 것처럼 보인다”고 밝혔다.

2007년 3월, 경제 붐이 한창이던 당시 원바자오(Wen Jiabao) 중국 총리는 평소 그답지 않은 우울한 기자 회견을 열었다. 원 총리는 중국의 성장 모델이 “불안정하고, 불균형하고, 조정되지 않으며, 지속 가능하지 않게 되었다”고 경고했다. 그러나 이 경고에는 그의 선견지명이 있었다. 이후 수년 동안 중국의 공식 GDP는 15%에서 6%로 떨어졌고, 이는 30년 만에 일어난 가장 느린 성장률이었다. 그리고 중국 경제는 현재 마오쩌둥 이후 시대의 가장 긴 둔화를 경험하고 있는 중이다.

사실, 6%의 성장률은 여전히 특별한 것으로 여겨질 수 있다. 미국 경제를 보라. 2008년부터 2016년까지 약 2%의 성장률에 정체되어 있었다. 그러나 많은 경제학자들은 중국의 실제 성장률은 공식 수치의 절반 이하라고 믿고 있다. 더욱이 GDP 성장이 반드시 더 큰 부로 전환되는 것도 아니다. 한 국가가 인프라 프로젝트에 수십억 달러를 쓰면 GDP가 상승할 것이다. 그러나 이 프로젝트가 ‘어디에도 연결되지 않는 다리(bridges to nowhere)’로 구성되어 있다면, 국가의 부는 그대로 유지되거나 혹은 감소할 것이다. 부를 축적하려면, 국가는 생산성을 높여야한다. 그러나 지난 10년간 중국에서 생산성 수치는 오히려 줄어들었다. 실제로 중국의 모든 GDP 성장은 정부가 부양 자본을 경제에 모두 투입한 결과이다. 이러한 정부의 부양 지출을 모두 뺀다면, 중국 경제는 전혀 성장하지 않고 있거나 심지어 후퇴하고 있는 것일 수도 있다.

비생산적 성장의 징후는 쉽게 발견된다. 중국은 사무실, 아파트, 쇼핑몰, 공항 등이 비어 있는 50개가 넘는 유령 도시를 건설했다. 전국적으로 주택의 20% 이상이 공실이다. 주요 산업의 초과 용량은 30%를 넘고 있다. 공장은 유휴 상태이고 창고에 쌓인 상품이 상하기도 한다. 이러한 낭비로 인한 전체 손실을 계산하기는 쉽지 않지만, 중국 정부조차도 2009년과 2014년 사이 불과 5년 만에 ‘비효율적 투자’로 6조 달러 이상이 사라졌다고 추정하고 있다. 더 나쁜 점은 중국의 부채가 지난 10년 동안 4배로 늘어났고, 현재 중국 GDP의 300%를 넘어선다는 점이다. 평화의 시대에, 그 어떤 국가도 이렇게 빠르게 국가 부채가 늘어난 사례가 없다.

여전히 더 최악은 한때 중국의 경제 상승을 견인한 자산이 부채로 빠르게 전환되고 있다는 것이다. 1990년대와 2000년대 초, 중국은 외국 시장과 기술에 대한 접근을 확대하는 것을 즐겼다. 중국은 식량, 수자원, 에너지 자원에서 거의 자급자족했으며, 역사상 가장 큰 인구배당효과(Demographic Dividend, 전체 인구에서 생산가능인구가 차지하는 비율이 높아져 부양률이 감소하고 경제성장이 촉진되는 효과)를 누리고 있었다. 현재의 중국은 외국 시장과 기술에 대한 접근을 잃고 있다. 물은 부족해졌고, 국가는 천연 자원을 훼손해오고 있으며, 다른 어떤 나라보다 더 많은 식량과 에너지를 수입하고 있다. 한 자녀 정책으로 중국은 역사상 최악의 ‘노령화’도 경험할 예정이다. 즉, 30년 내에 2억 명의 노동인구와 젊은 소비자층이 사라지고, 3억 명의 노령 인구를 얻게 될 것이다. 부채를 축적하는 국가는 예외 없이 생산성을 잃고, 10년 이상 경제 성장률이 거의 제로에 이르게 된다.

벡클리 교수는 강력하게 부상한 국가들이 정체기를 맞을 경우 위기가 온다고 말한다.

“중국과 같이 빠르게 성장하는 강대국들이 경제적 열기를 다 소진하면 곧바로 약세로 돌아서는 것은 아니다. 오히려 의욕적이고 공격적이 된다. 과거 급격한 성장은 국가적 야망을 일으켰고 시민의 기대를 높였으며, 경쟁 국가들을 괴롭혔다. 그러나 침체는 갑작스럽게 야망과 기대를 무너뜨리고, 적들에게는 반격의 기회를 제공한다. 불안감에 떠는 지도자들은 내부의 반대 세력을 억압한다. 꾸준한 성장을 회복하고 내부의 반대와 외부의 포식(predation)을 막기 위한 방법을 찾는다. 확장은 그러한 하나의 ? 새로운 부의 원천을 모색하고, 통치 체제 주변의 국가들을 모으고, 경쟁국들을 물리칠 수 있는 ? 기회를 제공한다.”

역사적 선례는 수없이 많다. 지난 150년 동안 약 10여 신흥 강대국들이 빠른 경제 성장을 경험한 후 오랜 시간 둔화되었다. 그러나 어느 누구도 변화된 ‘새로운 표준’을 조용히 받아들이지 않았다.

- 러시아는 19세기 후반 둔화를 겪었다. 차르는 자신의 권위를 강화하고 시베리아 횡단 철도를 건설하며 주변국들에 진출하는 것으로 이 둔화에 대응했다.

- 일본과 독일은 1차-2차 대전 사이에 경제 위기에 시달렸고, 두 국가는 권위주의 체제로 변하여 자원을 장악하고 외국 경쟁자를 격파하기 위해 광폭한 방법에 빠졌다.

- 프랑스에서는 전후 호황이 1970년대에 끝나고 있었다. 이후 프랑스는 아프리카에 그들의 경제적 영향력을 재구축하기 위해 이전 식민지에 14,000명의 병력을 배치하고 20년 동안 그 지역에서 수십 건의 군사 개입을 시도했다.

- 최근 2009년, 세계 유가가 폭락하자, 정체기를 맞이한 러시아는 주변 이웃 국가들에게 지역 경제 블록에 가입할 것을 강요했다. 수년 뒤, 이러한 강요 캠페인은 우크라이나에 ‘광장혁명’을, 러시아의 크림 반도 합병과 같은 분쟁을 촉발시켰다.

따라서 문제는 ‘신흥 강대국’이 해외로 확장을 시도할 것인지가 아니다. 그것은 역사가 보여주듯 신흥 강대국의 본능이다. 우리가 던져야 할 질문은 ‘그 확장이 어떤 형태를 취할 것인가?’이다. 해답은 부분적으로 글로벌 경제의 구조에 달려있다. 해외 시장은 얼마나 개방되어 있는가? 국제 무역 루트는 얼마나 안전한가? 이상적인 방식은 점차 둔화되고 있는 신흥 강대국이 평화적인 무역과 투자를 통해 경제를 다시 살리는 것이다. 그러나 그러한 길이 닫혀있다면 1930년대 독일과 일본이 그랬던 것처럼 강제로 다른 나라 시장에 진출하거나 중요한 자원을 강제로 확보하는 길로 나갈 수 있다.

그렇다면 앞으로 다가오는 슬럼프를 중국은 어떻게 처리할 것인가? 미국과 EU는 어떤 대응을 할까? 이 질문에 대한 답이 2020년대와 그 이후의 세계를 형성할 것이다. 우리는 다음과 같은 예측을 내려 본다.

첫째, 중국의 비약적인 상승을 가능하게 했던 초(hyper)-세계화의 시대는 이미 끝났다.

세계 경제는 이전보다 오늘날 더 개방되어 있지만, 미국과의 양자 무역 전쟁뿐만 아니라 세계적인 보호주의의 확대로 중국의 해외 시장과 자원에 대한 접근은 점점 더 위협을 받게 될 것이다. 미국과 유럽연합이 중국에게 국제 룰을 적용시킴에 따라 중국의 수월했던 여행은 이제 종언을 맞고 있다. 중국은 이제 철저하게 국제 룰에 의해 플레이를 하거나, 그렇지 않으면 글로벌 경제와 단절될 수 있다. 다국적 기업들은 이미 중국 주변에서 공급망의 상당한 부분을 재설정하는 것으로 이미 대응을 시작하고 있다.

둘째, 중국은 국내 경제 붕괴를 막기 위해 중상주의적 확장을 절반으로 줄일 것이다.

국가의 내부 경제 구조는 필연적으로 경기 둔화에 대한 반응으로 형성된다. 중국 정부는 수많은 국영 기업들을 보유하고 있고, 이 기업들은 중국에 실질적으로 영향을 미친다. 이러한 이유로, 중국 정부는 해외 경쟁자들로부터 이들 기업들을 보호하고 국내에서 수익이 줄어들면 해외 시장에 진출할 수 있도록 노력을 기울여왔다. 중국과 같은 국가 주도 경제는 둔화 중에도 자유화되지는 않을 것이다. 그렇게 하려면 중국 정부가 선호하는 기업 보조금과 자국 산업 보호 조치를 철회해야 한다. 만약 이러한 개혁을 단행한다면 파산, 실업의 증가뿐만 아니라 대중의 분노를 유발할 위험이 있다. 중국 경제의 자유화는 정권이 생존을 위해 의존하는 현재의 구조를 대폭 개편해야 하는 부담도 있다. 중국 정부는 아마도 불가피하게 기존 중상주의적 확장을 절반으로 줄이는 방향과 더불어, 해외 독점 경제 구역을 개척하고 외국 경쟁자로 대중의 분노를 돌리게 될 것이다.

셋째, 중국은 내부 탄압과 통제를 강화할 것이다.

중국의 최근 행동은 경제 불안에 대한 교과서적인 반응에 불과하다. 1990년대와 금세기 초반 중국 경제가 호황을 누리던 시기, 중국은 정치적 통제를 완화하고 경제 통합과 우호적 외교 관계를 통해 ‘평화로운 성장’을 추구할 것을 표방했다. 그러나 현재는 어떤가? 노동자들의 시위가 증가하고, 엘리트들은 돈과 자신의 자녀들을 중국으로부터 벗어나게 하고 있으며, 정부는 부정적인 경제 뉴스 보도를 금지하고 있다. 또한 중국 정부는 지난 10년간 내부 보안에 대한 지출을 두 배로 늘려 역사상 가장 강력한 선전 및 검열, 감시 시스템을 만들었다. 억류 수용소에 백만 명의 위구르족을 구금하고 시진핑 총리의 손에 권력을 집중시키고 있다. 홍콩 시위에 대해서도 평화적인 해결책보다는 진입을 할 명분을 기다리고 있다.

넷째, 중국은 해외에 힘을 과하시는 부문에 있어 더 큰 투자를 단행할 것이다.

중국은 군사 면에서 지난 10년간 영국 해군보다 더 많은 군함을 발주하여 배치해오고 있고, 아시아의 주요 해협을 수백 대의 군함과 항공기로 채우고 있다. 남중국해 전역에 군사 전초 기지를 세웠으며 종종 이웃 국가들과 영토 분쟁에서 제재를 활용하고, 선박 충돌 및 공중 요격에 대한 위기를 고조시키고 있다.

다섯째, 미국은 고유의 장점을 활용하여 중국의 상업, 외교, 군사 위협에 대응할 것이다.

국가 지도자들이 자국의 적법성과 국제적 영향력을 강화하는 데 있어 빠른 성장에 의존할 수밖에 없을 때, 내부의 반대 의견을 진압하고, 민족주의를 강조하고, 필요하다면 어떤 수단이든 활용하여 경제를 강화하고자 할 것이다. 간첩행위, 불공정 거래 관행, 남동 중국해에서의 해상 충돌, 대만과의 전쟁은 현재의 중국이 일으킬 수 있는 위협이 될 것이다. 이러한 중국의 움직임에 미국은 고유의 장점을 최대한 활용하여 중국을 계속 압박할 것이다. 이 과정에서 미국의 전략은 중국이 크게 반발하지 않는 범위에서 이러한 위협을 억제하는 것이다. 미국은 중국의 시도를 좌절시킴과 동시에 중국의 불안이 현실화되지 않도록 이중적인 조치를 취해야 한다. 이 목표에 있어 중요한 것은 올바른 이니셔티브를 확보하여, 적절한 균형을 유지하는 것이다.

여섯째, 홍콩은 중국이 새로운 현실을 다룰 수 있는지에 대한 첫 번째 테스트가 될 것이다.

지정학적 및 상업적 현실을 감안할 때, 미국은 이미 시진핑 총리에게 홍콩 사태에 중국이 개입했을 때 중국이 감내해야 하는 비용을 경고했을 것이다. 홍콩에는 이미 1,400여 개의 미국 기업들이 운영되고 있기 때문에, 중국이 홍콩을 단속하기 시작하는 경우 사태는 예상보다 훨씬 더 심각한 상황으로 빠져들 것이다. 미국은 세계에서 가장 경제적으로 활기찬 도시의 난민들을 이민자로서 환영할 수도 있다. 시진핑 총리 또한 중국 정부가 홍콩에 어떤 유형이든 제재를 가할 경우, 중국에 대한 국제적인 제재가 발생하고, 이는 대규모 관세와 연계된다는 점을 잘 알고 있다. 중국이 이러한 현실을 어떻게 파악하고 홍콩을 다룰지는 좀 더 지켜봐야 할 것이다.

* *

References List :

1. October 22, 2019. Derek Scissors. Is the U. S. economy pulling away from China?

https://www.aei.org/foreign-and-defense-policy/is-the-us-economy-pulling-away-from-chinas/

2. Bloomberg Opinion.July 23, 2019. Hal Brands. Every president since Reagan was wrong about China’s destiny.

https://www.bloomberg.com/opinion/articles/2019-07-23/every-president-since-reagan-was-wrong-about-china-s-destiny

3. Foreign Affairs.October 28, 2019. Michael Beckley. The United States Should Fear a Faltering China.

https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/china/2019-10-28/united-states-should-fear-faltering-china

4. Foreign Affairs.September 21, 2019. Michael Beckley. Stop Obsessing About China.

https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/china/2018-09-21/stop-obsessing-about-china

5. The Washington Post.Mark Thiessen. August 19, 2019. China does not have the upper hand in Hong Kong. Trump does.

https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/2019/08/15/china-does-not-have-upper-hand-hong-kong-trump-does/

6. The Hill. 08/14/19. GARY SCHMITT. Europe faces a security threat from the rise in Chinese military power.

https://thehill.com/opinion/international/457399-europe-faces-security-threat-from-the-rise-in-chinese-military-power

|  |

Managing a Faltering China

In Washington and other capitals around the world “the defining geopolitical story of our time is the slow death of U. S. hegemony in favor of a rising China. Harbingers of Beijing’s ascent are everywhere. China’s overseas investments span the globe. The Chinese navy patrols major sea lanes, while the country colonizes the South China Sea in slow-motion. The government cracks down on dissent at home, while administering a hefty dose of nationalist propaganda around the world.”

Yet, like so much of today’s conventional wisdom, this story does not stand up under scrutiny.

Beijing’s newfound assertiveness looks, at first glance, as the mark of growing power and ambition. But in fact, it is nothing of the sort. China’s actions reflect profound unease among the country’s leaders, as they contend with their country’s first sustained economic slowdown in a generation and they can discern no end in sight. China’s economic conditions have steadily worsened since the 2008 financial crisis. The country’s growth rate has fallen by half and is likely to plunge further in the years ahead, as debt, foreign protectionism, resource depletion, and rapid population aging take their toll.

But while China’s economic woes will make it a less competitive rival in the long term, they make it a greater threat to the United States, today. Why? As Michael Beckley recently explained in Foreign Affairs, “When rising powers have suffered such slowdowns in the past, they became more repressive at home and more aggressive abroad. China seems to be headed down just such a path.”

In March 2007, at the height of a years-long economic boom, then-Premier Wen Jiabao gave an uncharacteristically gloomy press conference. China’s growth model, Wen warned, had become “unsteady, unbalanced, uncoordinated, and unsustainable.” The warning was prescient: in the years since, China’s official gross domestic product growth rate has dropped from 15 percent to six percent - the slowest rate in 30 years. And China’s economy is now experiencing its longest deceleration of the post-Mao era.

If real, a growth rate of six percent could still be considered spectacular; the U.S. economy was stuck at a rate of around two percent from 2008 to 2016. But many economists believe that China’s true rate is less than half the official figure. Moreover, GDP growth does not necessarily translate into greater wealth. If a country spends billions of dollars on infrastructure projects, its GDP will rise. But if those projects consist of “bridges to nowhere,” the country’s stock of wealth will remain unchanged or even decline. To accumulate wealth, a country needs to increase its productivity - a measure that has actually dropped in China over the last decade. Practically all of China’s GDP growth has resulted from the government’s pumping capital into the economy. Subtract government stimulus spending and China’s economy may not be growing at all, or even shrinking.

The signs of unproductive growth are easy to spot. China has built more than 50 ghost cities - sprawling metropolises of empty offices, apartments, malls, and airports. Nationwide, more than 20 percent of homes are vacant. Excess capacity in major industries tops 30 percent: factories sit idle and goods rot in warehouses. Total losses from all this waste are difficult to calculate, but even China’s government estimates that it blew at least $6 trillion on “ineffective investment” in just five years between 2009 and 2014. Even worse, China’s debt quadrupled in absolute size over the last ten years and currently exceeds 300 percent of its GDP. No major country has ever racked up so much debt so fast, in peacetime.

Worse still, assets that once propelled China’s economic ascent are fast turning into liabilities. In the 1990s and early 2000s, the country enjoyed expanding access to foreign markets and technology. China was nearly self-sufficient in food, water, and energy resources, and it had the greatest demographic dividend in history, with eight working-age adults for every citizen aged 65 or older. Now China is losing access to foreign markets and technology. Water has become scarce, and the country is importing more food and energy than any other nation, having decimated its own natural resources. Thanks to the one-child policy, China is about to experience the worst “aging crisis” in history; it will lose 200 million workers and young consumers and gain 300 million seniors in the course of three decades. Any country that has accumulated debt lost productivity, or aged at anything close to China’s current clip has slipped to near-zero economic growth for at least a decade.

As Beckley explains, “When fast-growing great powers like China run out of economic steam, they typically do not mellow out. Rather, they become prickly and aggressive. Rapid growth has fueled their ambitions, raised their citizens’ expectations, and unnerved their rivals. Suddenly, stagnation dashes those ambitions and expectations while giving enemies a chance to pounce. Fearful of unrest, leaders crackdown on domestic dissent. They search feverishly for ways to restore steady growth and keep internal opposition and foreign predation at bay. Expansion presents one such opportunity - a chance to seek new sources of wealth, rally the nation around the ruling regime, and ward off rival powers.”

Historical precedents are numerous. Over the past 150 years, nearly a dozen great powers experienced rapid economic growth followed by long slowdowns. None accepted the “new normal” quietly.

- S. growth plummeted in the late nineteenth century, and Washington reacted by violently suppressing labor strikes at home while pumping investment and exports into Latin America and East Asia, annexing territory there and building a gigantic navy to protect its far-flung assets.

- Russia, too, had a late-nineteenth-century slowdown. The Tsar responded by consolidating his authority, building the Trans-Siberian Railway, and occupying parts of Korea and Manchuria.

- Japan and Germany suffered economic crises during the interwar year and both countries turned to authoritarianism and went on rampages to seize resources and smash foreign rivals.

- France had a postwar boom that fizzled in the 1970s: the French government then tried to reconstitute its economic sphere of influence in Africa, deploying 14,000 troops in its former colonies and embarking on a dozen military interventions there over the next two decades. And

- As recently as 2009, world oil prices collapsed, which led a stagnating Russia to pressure its neighbors to join a regional trade bloc. A few years later, that campaign of coercion spurred Ukraine’s “Maidan revolution” and Russia’s annexation of Crimea.

The question, then, is not whether a struggling “rising power” will try to expand abroad, but what form that expansion will take. The answer depends in part on the structure of the global economy. How open foreign markets are? And How safe international trade routes are? If circumstances allow it, a slowing great power might be able to rejuvenate its economy through peaceful trade and investment, as Japan tried to do after its postwar economic miracle came to an end in the 1970s. If that path is closed, however, then the country in question may have to push its way into foreign markets or secure critical resources by force - as Japan did in the 1930s.

Like so many trends rooted in demography and human behavior, this one can be influenced by technology but remains largely irreversible. How will China handle the coming slump? How will the U. S. and EU respond? The answers will shape the global reality in the 2020s and beyond.

Given this trend, we offer the following forecasts for your consideration.

First, the era of hyper-globalization that enabled China’s extraordinary rise is over.

While the global economy is still more open today than prior to the 21st century, a global rise in protectionism, as well as the bilateral trade war with the United States, increasingly threatens China’s access to foreign markets and resources. China’s “free ride” at the expense of American and EU producers is over. China will be forced to play by international rules or be cut-off from the global economy. Multi-national corporations are already responding by rerouting an increasing portion of their supply-chains around China.

Second, China will double down on mercantilist expansion in an effort to keep the domestic economy from collapsing.

The structure of a country’s home economy inevitably shapes its response to a slowdown. The Chinese government owns many of the country’s major firms, and those firms substantially influence the state. For this reason, the government will go to great lengths to shield these companies from foreign competition and help them conquer overseas markets when profits dry up at home. A state-led economy like China’s will not liberalize during a slowdown. Doing so would require eliminating subsidies and protections for state-favored firms; such reforms risk instigating a surge in bankruptcies, unemployment, and popular resentment. Liberalization of China’s economy would also disrupt the crony-capitalist networks that the regime depends on for survival. Regimes like China’s inevitably will double-down on mercantilist expansion, using money and muscle to carve out exclusive economic zones abroad and divert popular anger toward foreign enemies.

Third, China will ramp up domestic repression and control.

China’s recent behavior is a textbook response to economic insecurity. Back in the 1990s and the early years of this century, when the country’s economy was booming, China loosened political controls and announced to the world that its “peaceful rise,” would be pursued through economic integration and friendly diplomatic relations. Compare the situation today: labor protests are on the rise, elites have been moving their money and children out of the country en masse, and the government has outlawed the reporting of negative economic news. President Xi Jinping has given multiple internal speeches warning party members of the potential for a Soviet-style collapse. Furthermore, the government has doubled internal security spending over the past decade, creating the most advanced propaganda, censorship, and surveillance systems in history. It has detained one million Uighurs in internment camps and concentrated power in the hands of a “dictator for life.” State propaganda blames setbacks, such as the 2015 stock market collapse and the 2019 Hong Kong protests, on Western meddling. These are not the actions of a confident superpower.

Fourth, China will increasingly invest in the mechanisms for projecting power abroad.

On the military front, it launched more new warships over the past decade than the whole British navy operates it and flooded major sea lanes in Asia with hundreds of government vessels and aircraft. It has built military outposts across the South China Sea and frequently resorts to sanctions, ship-ramming, and aerial intercepts in territorial disputes with its neighbors.

Fifth, the United States will counter Chinese commercial, diplomatic and military threats by leveraging its inherent advantages.

When the country’s leaders cannot rely on rapid growth to bolster their domestic legitimacy and international clout, they will be all the more eager to squelch dissent, burnish their nationalist credentials, and boost the economy by any means necessary. Rampant espionage, unfair trade practices, naval clashes in the East and South China Seas, and a war over Taiwan are only the most obvious risks that a desperate and flailing China will pose. U. S. statecraft will seek to contain these risks without causing China to lash out in the process. To that end, Washington will have to deter Chinese aggression, assuage China’s insecurities, and insulate the United States from blowback should deterrence and reassurance fail. The inherent tension among these objectives will make the task a very difficult one. The right initiatives could help it strike the proper balance. And,

Sixth, Hong Kong will serve the first big test of whether China can deal with the new realities.

Given the geopolitical and commercial realities, the Trends editors believe that the State Department has already warned Xi that the cost of military intervention will be capital flight, brain drain and the end of Hong Kong’s preferential trade status, as well as any hopes of a satisfactory bi-lateral trade deal. Specifically, if he launches a crackdown in Hong Kong, then the United States will repeal the Hong Kong Policy Act, largely eliminating the rationale for nearly 1,400 U. S. businesses to operate in Hong Kong. The United States will also welcome Hongkongers as refugees from the most economically vibrant city on Earth; these hard-working, creative, entrepreneurial people are precisely the kind of immigrants Trump has said he wants to come into our country. Xi also knows that China would face massive tariffs and international sanctions that could send its economy into full contraction causing the kind of instability and protests on the mainland that the Communist Party of China wants to avoid at all costs. In short, a military operation, even if it succeeded, would be a Pyrrhic victory. The question now is, “How does China put the “Hong Kong genie,” back in the bottle?”

References

1. October 22, 2019. Derek Scissors. Is the U. S. economy pulling away from China?

https://www.aei.org/foreign-and-defense-policy/is-the-us-economy-pulling-away-from-chinas/

2. Bloomberg Opinion.July 23, 2019. Hal Brands. Every president since Reagan was wrong about China’s destiny.

3. Foreign Affairs.October 28, 2019. Michael Beckley. The United States Should Fear a Faltering China.

https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/china/2019-10-28/united-states-should-fear-faltering-china

4. Foreign Affairs.September 21, 2019. Michael Beckley. Stop Obsessing About China.

https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/china/2018-09-21/stop-obsessing-about-china

5. The Washington Post.Mark Thiessen. August 19, 2019. China does not have the upper hand in Hong Kong. Trump does.

6. The Hill. 08/14/19. GARY SCHMITT. Europe faces a security threat from the rise in Chinese military power.